In one sense the answer to the question posed in the panel’s title is clear. The responsive city is a fiction. It doesn’t exist, and it may not ever exist, except in our imagination. Thank you for coming.

But seriously, whether it is fact or fiction, of course, begs the question of what is a responsive city.

One way to answer that question is to read and absorb the Situated Technologies Pamphlet Series, for which Mark Shepard is a co-editor along with Omar Khan and Trebor Scholz. As they write in the introduction to the first volume of the series,

“How will the ability to design increas-ingly responsive environments alter the ways we conceive of space? What do architects need to know about urban computing, and what do technologists need to know about cities? How are these issues themselves situated within larger social, cultural, environmental, and political concerns?”

I am certain this panel will shed some light on these questions today.

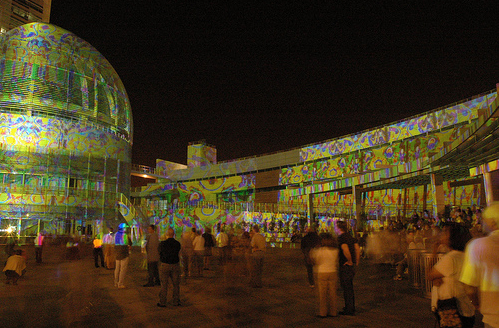

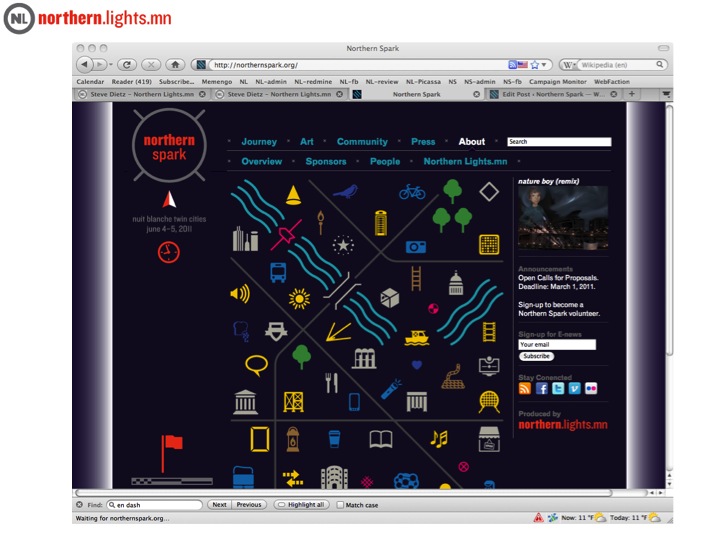

I am neither a practitioner nor a theorist, but the ideas of the responsive city have animated my curatorial practice at least since 2004, when I proposed the 13th ISEA Symposium – which was held in 2006 in San Jose – have as one of its themes the “Interactive City.” Working with Eric Paulos and a stellar steering committee of artists and thinkers, we acknowledged the slipperiness of the thematic in its call for projects relating to the following topics: Shadow City, Collaborative Challenge, Hybrid Histories, Non-Places, Alternate Playgrounds, Urban Archaeology, Exposed City, Open Traversal, Operational City, Hacked City, Parasitic City, Open Source City, Alternate Economies, Town Hall, Community Mapping, and Parallel Cities.

For every 01SJ Biennial since and for many projects in between, I have worked with a wide range of artists and architects, whose projects are what Julian Bleecker has referred to as “design fictions” for the responsive – or in Mark’s more felicitous phrasing, sentient – city.

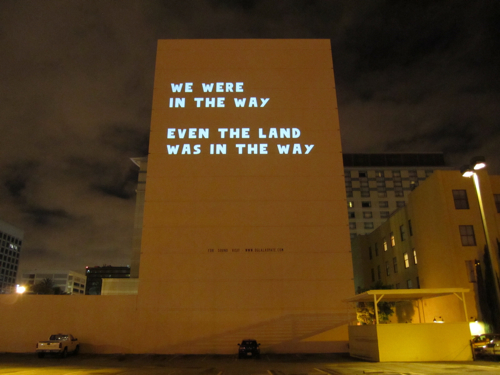

What I was interested in proposing today’s particular panel was not only using artists’ practice as a lens to view the debates swirling around the theories and concerns and prognostications about the responsive city, but also to look at work that has gone beyond the thrill of the design probe to instantiation in the fabric of the city. As a producer as well as a curator, I’m interested in that territory that I suppose could be likened to the “value engineering” phase of a building project. Which in my experience, too often means taking out all the cool stuff that animated the project in the first place. Yet, against all odds, our panelists have succeeded in instantiating some amazing projects – which, of course, does not mean there aren’t questions about them or about what they might do “next time.”

So, without further ado, I will briefly introduce each panelist, who will then speak for about 18 minutes, followed by a response from Mark Shepard, after which there may be time for some questions from the audience – or perhaps fisticuffs on the panel. That would be exciting.

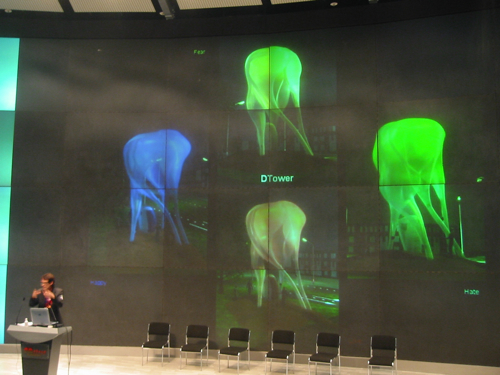

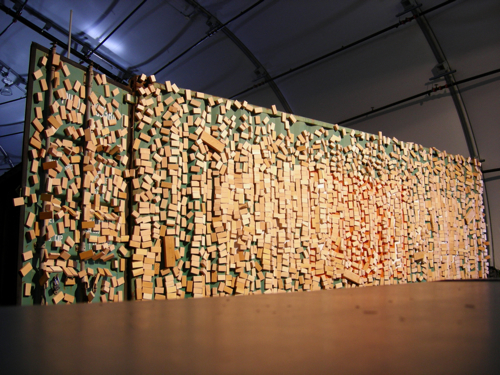

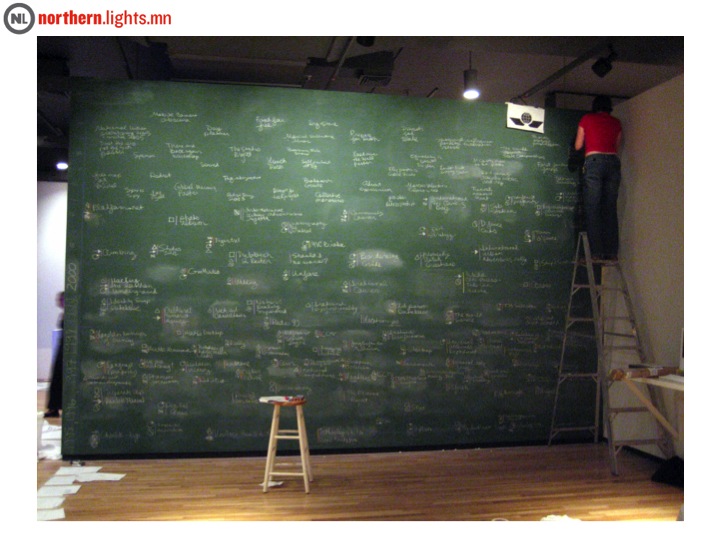

Ben Rubin is a media artist based in New York City. Rubin’s work is in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the San Jose Museum of Art, and the Science Museum, London, and has been shown at the Whitney Museum in New York, the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, and the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe. Rubin has created large-scale public artworks for the New York Times, the city of San Jose, and the Minneapolis Public Library.

I consider Ben’s Listening Post, with Mark Hansen, to be one of the most significant works of art, in any medium, of the 21st century, and I think it is remarkable that its cousin, Moveable Type, is on permanent, changing display at the New York Times building just down the road. Ben also has a show at Bryce Wolkowitz gallery, which you should see before you leave town, if you haven’t.

Barbara Goldstein is the Public Art Director for the City of San Jose Office of Cultural Affairs and the editor of Public Art by the Book, a primer recently published by Americans for the Arts and the University of Washington Press. Prior to her work in San Jose, Goldstein was Public Art Director for the City of Seattle. Goldstein has worked as a cultural planner, architectural and art critic, editor and publisher. She has written for art and architectural magazines and lectured on public art both nationally and internationally. She is currently Chair of the Public Art Network for Americans for the Arts.

Barbara has been a colleague and collaborator for each of the 01SJ Biennials, and the public art master plan [pdf] she instigated for public art at the San Jose Airport is, for me, is a model or at least pointer to how to think about creating the “rules” to enable an engaging responsive city to emerge.

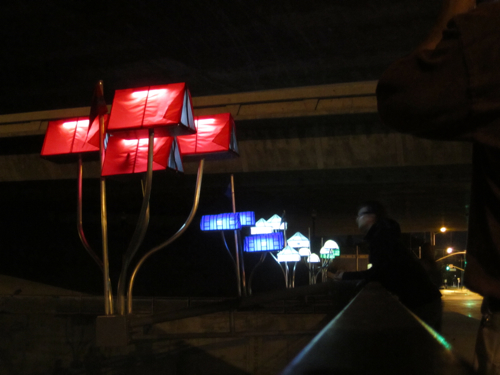

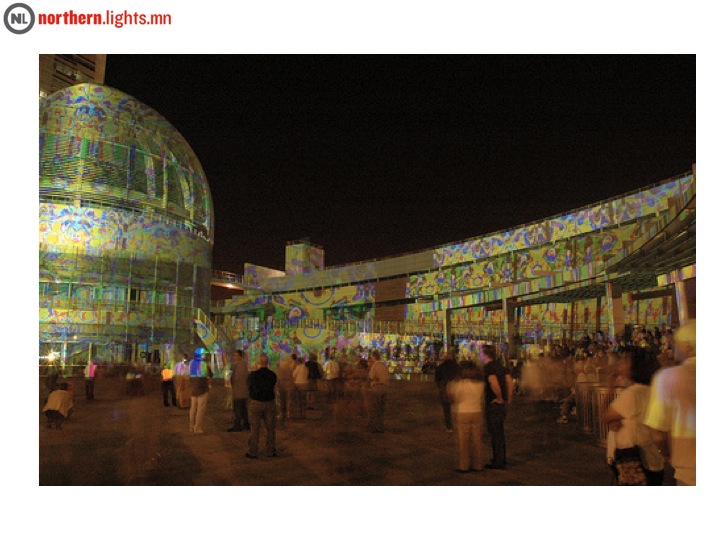

Cameron McNall is an Architect and Principal of the group Electroland. Every Electroland project is site-specific and may employ a broad range of media, including light, sound, images, motion, architecture, interactivity, and information design. Electroland works at the forefront of new technologies to create interactive experiences where visitors can interact with buildings, spaces and each other in new and exciting ways. A pop sensibility, expressed through whimsy and play, helps Electroland to achieve projects that are accessible and that invite visitor participation.

I have not had the pleasure of working, yet, with Cameron, but at least he now returns most of my emails, and I have always admired the range of Electroland’s work from shadow billboards to frenetic facades and the layered complexity behind each project.

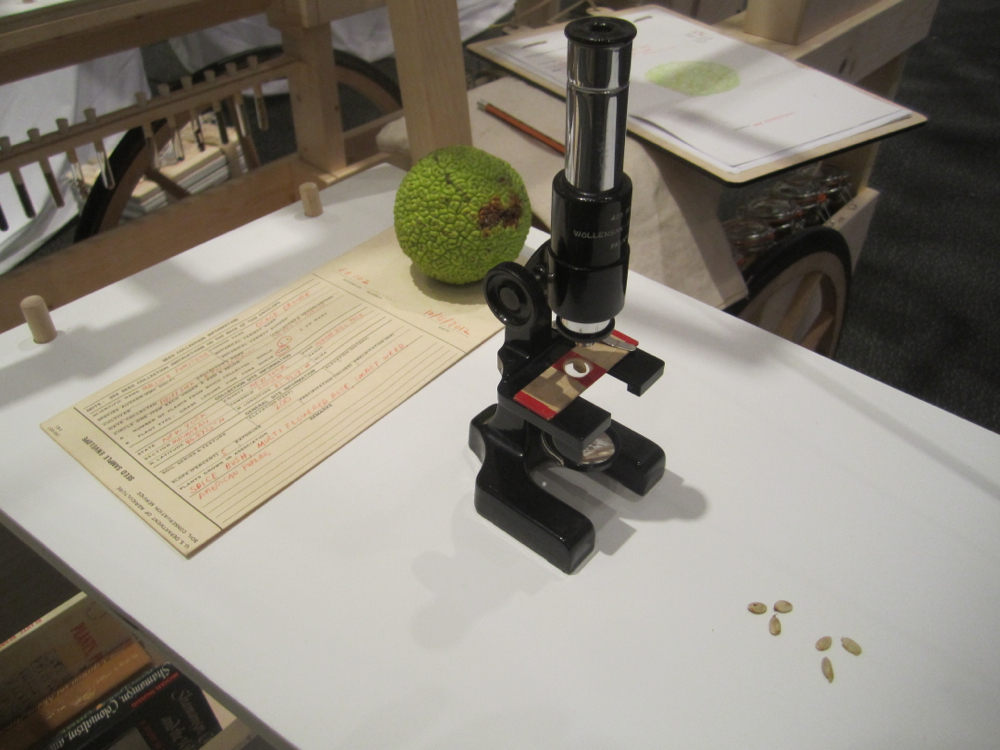

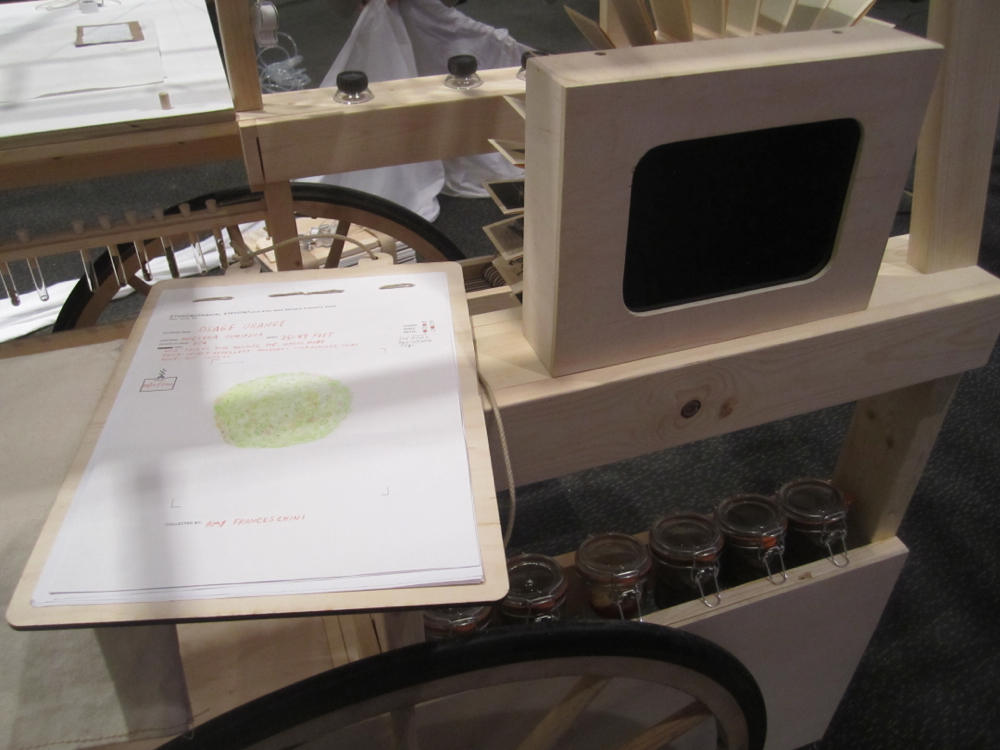

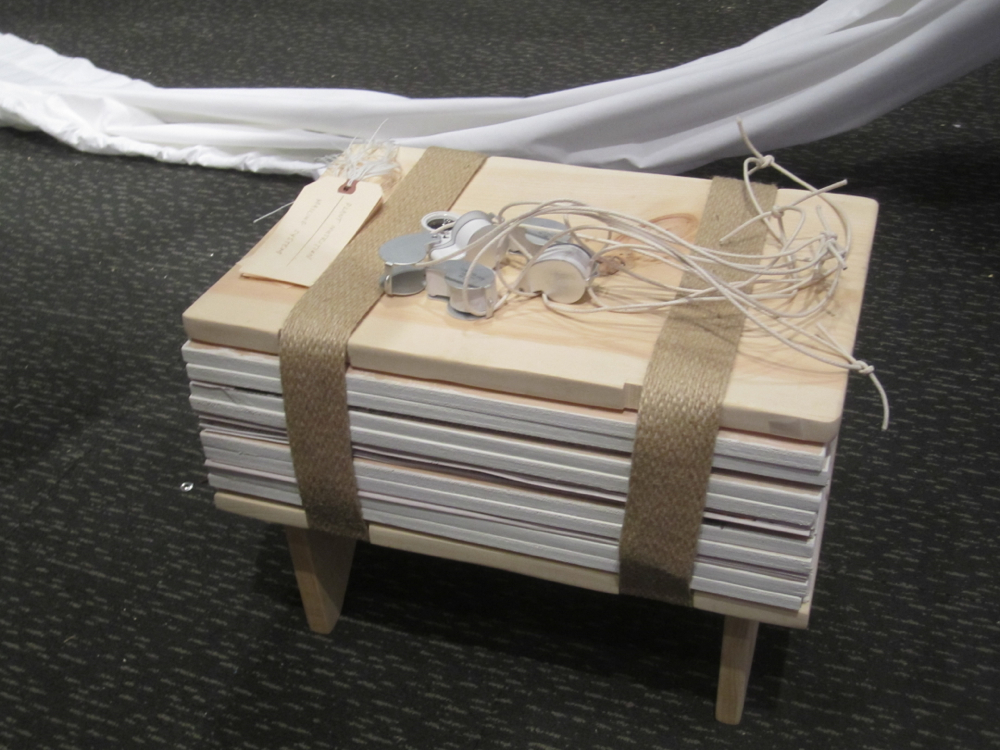

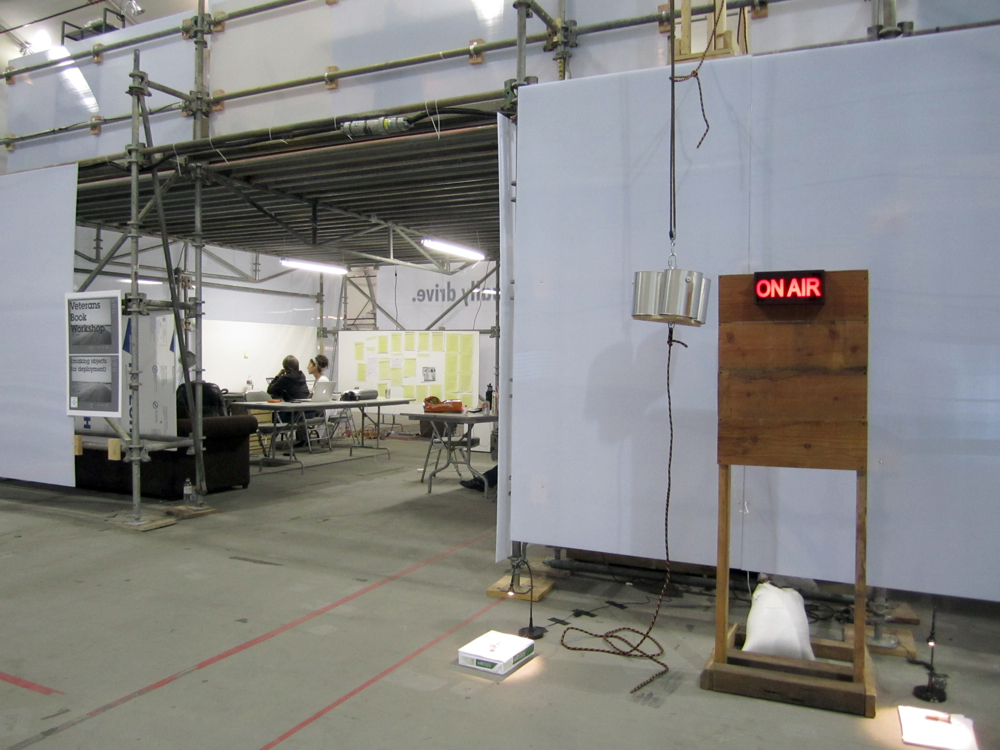

Mark Shepard is an artist, architect and researcher whose post-disciplinary practice addresses new social spaces and signifying structures of contemporary network culture. His current research investigates the implications of mobile and pervasive media, communication and information technologies for architecture and urbanism. Recent works include the Sentient City Survival Kit, a collection of artifacts for survival in the near-future sentient city; and the Tactical Sound Garden [TSG] – which he did present at the aforementioned ISEA/01SJ Biennnial in San Jose – an open source software platform for cultivating virtual sound gardens in urban public space. In 2009, he curated “Toward the Sentient City,” an exhibition of commissioned projects that critically explored the evolving relationship between ubiquitous computing and the city. He is the editor of Sentient City: ubiquitous computing, architecture and the future of urban space, published by the Architectural League of New York and MIT Press.

Mark’s writing and programming as well as his art have all been important influences on my own thinking and practice. There will be a book launch event tomorrow evening at McNally Jackson books, and I think it’s worth noting in the context of this panel that the book, Sentient City will also feature a special “heat sensitive” cover which will change color when exposed to sunlight or touch!

Please welcome Ben Rubin.