by Stephen R. Miller

The Egg and the Sperm are a matter of prosaic beginnings. They meet in passion, lust, happiness, joy; in individuals coupled to each other. They can meet through violence; they can be frozen and shipped like cargo. Are they commodities sans soul? The conversation rapidly evokes larger questions. “Manhood’s repose of If,” as Herman Melville says in Moby Dick, is shaken by the subject. Adding to this existential ambivalence, the egg and sperm reference not only life but after life; Marilynne Robinson writes in Gilead: “We participate in Being without Remainder.” T.S. Eliot reminds us that the egg and sperm’s passage, the passage of a journey, is also the passage of time: “To arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” (Little Gidding)

Janaki Ranpura’s Egg and Sperm Ride explores the riddle of egg and sperm in a multi-stage performance art work composed of: a cross-country ride by Ranpura in a costumed Egg bicycle; a series of bicycle ballets in the street starring an Egg tricycle and a number of Sperm bicycle riders; and a series of exhibitions of the Egg tricycle and the glowing helmets of the Sperm riders designed by her.

Whether on the cross-country Egg bicycle, or the performance ballet Egg tricycle, Ranpura rides the Egg, and is the mind of the Egg. From this vantage, she has choreographed experiences–both for street audiences and for audience-participating Sperm–that give physical voice to the ruminative questions of our essence. She does so with a dose of folly, joy, and celebration that make each performance dynamic in addition to its more ponderous questions.

In San Jose’s 01SJ Green Prix parade, Ranpura choreographed a bicycle ballet, called “the Wiggle,” for approximately ten cast members. Ranpura was the Egg, and the rest of the well-chosen cast– doctors, lawyers, radio personalities, and actors–were Sperm on bikes. The ballet began with the simple premise that the Egg was to be chased. Ranpura, as the Egg itself, raced ahead of the Sperm. Meanwhile, a gatekeeper corralled the Sperm, taunting them about their lusty itch and their almost certain fate. The Sperm, bursting with life, wrestled among each other (elbows thrown, hair pulled, wedgies given) for position. With a stock car-race flourish, the gatekeeper threw a flag and released the Sperm to their destiny. Each Sperm was dressed in black, with red lipstick, on a bicycle and wearing Ranpura’s electroluminescent, whimsical Sperm helmets with tails that bucked and curved during the chase.

More Sperm circling

In time, the Egg was captured and forced to stop. The Sperm swarmed about the Egg clockwise, and the Egg spun on its axis the other way in a bicycling pas de deux, the Sperm moving as one mass of blurred mayhem about the Egg’s giant, swirling solemnity. Three times around the Egg the Sperm went until, with a vigorous flourish and the ring of a bicycle bell, the Egg shook on its wheels, the Egg’s bamboo reeds rustled with conviction, and the Egg escaped with Ranpura inside. The stage was re-set, and the ballet performed multiple times over the course of the parade route.

Author as Sperm

I participated in the parade as a Sperm and chased after the elusive Egg, though in life Janaki has long been one of my closest friends and confidantes. Knowing her for so long, I could not help but notice that the Egg escapes in her dance, every time, and wonder what significance that might have. For though the Egg appears as an impenetrable eggish bamboo mass, there is a slippery, small entry in the back through which a Sperm might easily pass. The Sperm might find itself inside the Egg with Ranpura, together in that vulnerable space, the former fortress now a prison, or a home. When Ranpura says the Egg and Sperm Ride is about love, I can’t help but think that the physical manifestation of her question is some Sperm slipping its way, unexpectedly, into her Egg, and the moment of recognition she might have at suddenly having company.

In practice, Ranpura has let plenty of people inside her Egg. While displaying it in an exposition hall before the parade, or on the street after the parade, a ride in the Egg was a constant wish of children and adults alike. One passerby told Ranpura the dance would be a good abstinence education tool, which is one way to think of it, though the ready access to the Egg, upon close inspection, appears to send an inconclusive message. Rather, I believe Ranpura’s ballet evokes something that has dogged her for a long time: the nature of freedom and its quest. It is ironic, then, that Ranpura would take on this role as an Egg, when it is the Sperm who are notorious for their travels. Don’t they tell us, it is always the sperm swimming and the egg standing still? Not so in this piece by Ranpura.

Both versions of the Egg bike, cross-country (right) and San Jose Green Prix (left)

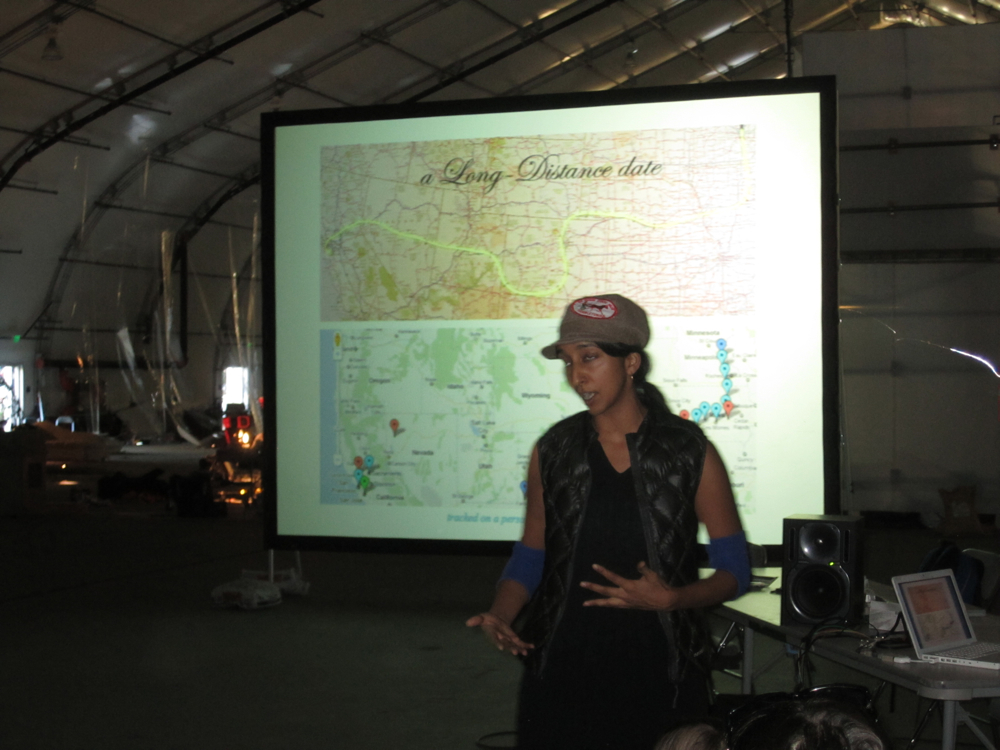

The other component of the artwork was a planned ride on a recumbent Egg bike from Minneapolis, Minnesota–where Ranpura currently resides–to San Jose, California, which was the site of the parade. Ranpura set forth on July 8, 2010, for the lonely journey but also posted to a blog about her thoughts as she traveled. Nine days in, Ranpura’s Egg bike was hit by a truck on a remote Nebraska byway. She made it to Denver and re-routed.

The Egg ride, like the Wiggle, evokes Ranpura’s inversion of what is Sperm and what is Egg, and evokes even further questions of her own wanderlust, perseverance, skills transcending gender roles, and her tireless heeding of the road that a generation ago was the province mostly of Kerouac and men who wanted to give it all up and live rough, if only to have said they lived. But Ranpura’s wanderlust–an Ohio native, she studied at Yale and in performance art schools in Paris and California and has performed throughout the world since–has never seemed to be about escape so much as learning. The Egg and Sperm Ride, gendered as it is, gives the Egg the chance to hold the handlebars, to choose the route, to be both the dancer and the dance. More than a feminist Egg, more than an Egg gone Sperm, Ranpura’s Egg breaks free of biology, free of convention, and forces us to grapple with what we can make of such an Egg that does not wait, but itself is a traveler in a digital age where distance is not always as it appears.

Stephen R. Miller is an attorney and writer living in San Francisco, California.