Schloss Leopoldskron, Salzburg, Austria

Schloss Leopoldskron, Salzburg, Austria

With Northern Lights.mn’s decision to devote the next two years of Northern Spark and related year-round programming to the effects of climate change under the rubric Climate Chaos | Climate Rising, team, we have been thinking a lot about the possible relations of art and artists to the future of humanity.

I was thrilled, therefore, to get the opportunity recently, with the support of the Bush Foundation, to attend a Salzburg Global Seminar (the 561st since 1947), Beyond Green: The Arts as a Catalyst for Sustainability. With a worldwide roster of incredibly accomplished attendees, it promised to be fertile grounds for research and thoughtful discussion.

Reading List

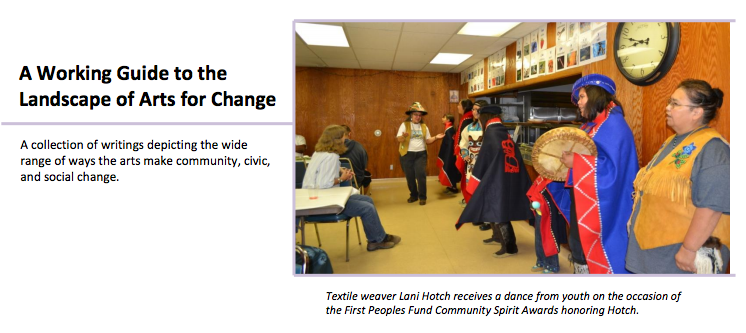

Seminar attendees were asked to provide links to resources about the arts and sustainability, and these ranged from “A Good Life in a Sustainable Nordic Region. Nordic Strategy for Sustainable Development.Nordic Council of Ministers” to “Local Plant Knowledge for Livelihoods: An Ethnobotanical Survey in the Garhwal Himalaya, Uttarakhand, India” to “The Spirit of Sovereignty Woven into the Fabric of Tribal Communities: Culture Bearers As Agents of Change.” In other words from policy documents to research findings to documentation of artists’ projects.

One unsurprising thing that comes through in much of the reading is the amazing lack of broadly articulated cultural policy in the United States compared to almost anywhere else in the world. What would it be like to live in a country where arts and culture are enshrined as pillars of development, such as in countries that take the U.N’s Agenda 21 as a legitimate document? What would it be like to not have to justify art as something more than an economic driver – as important and valuable as that is? I am not so naive as to believe that everything is hunky dory elsewhere, but the starting points of the value(s) of arts and culture are so different in some countries, and that’s a difference that makes a difference. That’s a difference that could be a matter of societal resilience in the face of the inevitable effects of climate change.

One of the most fascinating readings, which really attempted to tackle some of the underlying and debatable philosophical principles at stake, was Adrienne Goehler’s “Conceptual Thoughts on Establishing a Fund for Aesthetics and Sustainability.” Her broad set of drivers for the necessity such funding included “ten imperatives”: democratize, think and act, liberate, spawn, become fluid, listen and observe and publicize, charge, perceive, combine and link, admit.

One thing that Goehler emphasized, which is near and dear to team Northern Lights is that

“Sustainability is not understood by individuals as a space of possibility because it is not yet linked to the sensuality and passion of personal action, but is still mainly seen as an appeal to the superego or the well-filled wallet.”

and of course, we are in solidarity with:

“Sustainability is the result of thinking new things and seeing the familiar from a new perspective.”

She even takes on the relevance of the policies I was lusting for earlier:

“The sustainability debate and their advocates, the Agenda 21 initiatives are clearly stuck in a dead end because in spite of their comprehensive, indeed holistic, approach, they are still perceived as being restricted largely to the field of ecology, and they themselves do not understand sustainability as a genuinely cultural challenge. … [According to the Tutzinger Manifesto] in order to make sustainability a life force, ‘it is critical to integrate participants with the ability to bring ideas, visions, and existential experiences alive in socially recognizable symbols, rituals, and practices.’”

As we like to say at team Northern Lights: ““People need facts to make informed decisions, but it’s stories and culture that change people’s minds—and behavior. Artists create connection points to issues that may seem tired or impossibly contentious. We follow them in through beauty, wonder, and curiosity and quickly find ourselves engaged in a complex issue seen differently.”

What follows is not intended to be complete in any way. A formal report of the Seminar will be published in the near future, and these represent an inadequate sampling of some highlights.

Artists Inspiring Change

For the opening conversation of the Seminar, Kalyanee Mam, spoke about her film A River Changes Course, which was the winner of the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Documentary at Sundance, and “tells the story of three families living in contemporary Cambodia as they face hard choices forced by rapid development and struggle to maintain their traditional ways of life as the modern world closes in around them.” And Frances Whitehead gave a version of her Plenary talk for Cultures In Sustainable Futures in Helsinki, which covered such work as The Embedded Artist Project, Slow Clean-Up, and a long term project The 606.

The work and presentations seemed so different – personal, documentary, pov and systematic, theoretic, interventionist – that at first blush it was hard to imagine where the conversation could crossover. One comment, however, put into perspective a lesson that would be repeated over and over during the week. Kaly’s work was, in essence, about pre-development or “during-development,” and Frances’s about a post-development situation. Two sides of the same coin. The forests and fisheries of Cambodia had not yet been completely devastated, but the trajectory was clear, and in Chicago and Gary, nature had to be reintroduced into the industrialized, designed, built-on landscape. How can what has happened in the North be in dialog with the majority world, which is all too often the downstream recipient of our actions? What do we both need to learn?

Shahidul Alam spoke of his photography in the service of political consequences and made the appropriately pointed point about not feeling any less “developed” or almost any other term that is applied to Bangladesh all the time. He lives in the “majority world,” and it is important that this is recognized. As he put it at one point: “Until lions find their storyteller, stories about hunting will always glorify the hunter.” And the storyteller – as we learned more about later – often works through analogy. Shahidul spoke about the careful planning that went into an apparently innocent photography exhibit that included a photograph of a rice paddy. Beautiful and “benign” seeming, the title of the exhibition, “Crossfire” provided a completely different context for the people of Bangladesh, who were experiencing a horror of extra-judicial killings at the time.

In the afternoon, Pireeni Sundaralingam, a poet and neuroscientist, spoke mostly from the neuroscience side of her brain brain about if we’re truly trying to change people’s behavior, what do we know about behavior and how to change it from an experimental perspective?

Things That Don’t Work

- Repeat messaging

- Appeals to logic

- Arguments based on the lack of time in the future

- High intensity emotional messaging

Let me repeat that…

Needless to say, everyone of us has likely used each of these techniques to reinforce our messaging about the urgency of climate change. Pireeni went through a series of hilarious and sobering experiments, mostly in the last decade, which essentially proved the ineffectiveness of each of these strategies.

So what does work? I was unable to capture all of the points Pireeni made, but one critical one is simple: the brain is an analogy device. The brain, from a behavioral point of view, is nothing like a logic machine. It responds to analogies and metaphor, like the language found in poetry or photography or art. If we want to change people’s behavior, ultimately it will be through stories and analogies and metaphor: art. Not repeated warnings about the coming disaster and what a logical response would be.

Enlightening.

The City As a Driver of Change

On Day 3, we shifted from a focus on individual projects to more systemic responses, particularly in relation to the city as the site of more than 50% of the world’s population.

There were great presentations all day long from artists, policymakers, and activists around the world, but I want to call out some notes of the talk by Marco Kusumawijaya, Director, Rujak Centre for Urban Studies, Jakarta, Indonesia. Like many of the speakers, he reinforced the dictum that sustainability is a cultural problem, but he also suggested that the city – thinking of it as a cultural platform, almost – could and should be concerned with more than development. He referred to the “brutality of development.” The city should be a driver for solidarity and equity as well as a critique of nationalism and globalization. Development in this context should be building more commons. The centerpiece of community is the commons. Simple, really, but felt like an amazing lever to wrest the conversation away from all the arts and economic development palaver, especially in the United States.

Encouraging Bolder Policymaking

Not only does much of the rest of the world have cultural policymaking, but they are self-reflective about how to make it bolder!

Camilla Bausch, who is a long-standing member of the German delegation to the United Nations climate negotiations made particularly heartening comments about the how of bolder policymaking, suggesting that after the failure of Copenhagen, state actors realized they cannot do it alone regarding what needs to be done about climate change. Even at the policy level, non-state actors are critical. For example, the COP21 designated negotiators for COP21 in Paris never would have moved to 1.5 degree temperature rise as the maximum goal, if it wasn’t for the external pressure – then and the months and years leading up to Paris – of non-state actors. Projects like Climate Chaos | Climate Rising are important not only in terms of individual behavior and systems intervention but also as both goad and support for bolder policymaking.

We Are What We Eat

The last program I want to mention was a “fireside chat” moderated, passionately, by Pavlos Georgiadis, an Ethnobotanist, AgriFood Author & Climate Tracker.

Prairie Rose Seminole, a Prevention Specialist for The Boys and Girls Club of the Three Affiliated

Tribes, New Town, ND, gave a sobering presentation about the food deserts so common on Indian reservations and the endemic health problems that this gives rise to. At the same time, there is a bountiful history of traditional foods and healing that Prairie Rose is dedicated to reinvigorating, serving us all a tea o fBear root (osha root), bergamot and grey sage.

Kamal Mouzawak is the founder of Souk el Tayeb, Beirut. Nominally the first farmers market in Lebanon, in reality it is a way for a fractured community to come together to prepare meals and eat together. Tayeb holds several meanings in Arabic: “good”, “tasty” and “goodhearted” when talking about a person. Over time, Souk el Tayeb participants’ shared humanity becomes more important than their different ethnicities and religions and good and tasty food becomes an appreciation for goodhearted people.

Rounding out the panel, journalist, activist, and film director David Gross spoke about his project Wastecooking. Inspired by the sad fact that the food thrown away in Europe alone would be enough to feed all of the world’s hungry twice over, David “has whipped up a five-part web series and regularly organizes cook-ins and performances in public spaces that serve up a critical stance on consumerism.” Sadly, we did not get to try his Apple Compote a la Dumpster Diver, but you can find the recipe here, if you are interested.

Participants

Thanks to everyone for their generous participation and sharing of knowledge and experience: Shahidul Alam, Natasha Athanasiadou, Camilla C. Bausch, Fatima Zahra Bousso-Kane, Catherine Cullen, Teresa Dillon, Cecily Engelhart, Carolina Ferres, Torben Florkemeier, Alexis Frasz, Pavlos Georgiadis, Christine Gitau, Rebecca Kneale Gould, David M. Gross, Marcus Hagermann, Etelle Higonnet, Singh Intrachooto, Seitu Jones, Vrouyr Joubanian, Sofie Regitze Kattrup, Oleg Koefoed, Marco Kusumawijaya, Thomas Layer-Wagner, Brandie N. Macdonald, Kalyanee Mam, Anee-Marie Meister, Zayd Minty, Kamal Mouzawak, Thiago Ackel (Mundano), Omar Nagati, Chukwudum Odenigbo, Yasmine Ostendorf, Kajsa Li Paludan, Rachel Plattus, Robert Praxmarer, Michael Premo, Ferdinand Richard, Anais Roesch, Ania Rok, Alain Ruche, Rachel Schragis, Anupama Sekhar, Prairie Rose Seminole, Margaret Shiu, Holly Sidford, Regina R. Smith, Francis A. Sollano, Pireeni Sundaralingam, Elizabeth Thompson, Alison Tickell, Christian Biaus, Ben Twist, Anamaria Vrabie, Frances Whitehead, Rise Wilson.

Support

Thanks to the Bush Foundation, which supported my attendance at Beyond Green, to the Salzburg Global Seminar for organizing the event, and to Edward T. Cone Foundation, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Bush Foundation, and Red Bull Amaphiko for their support of the event.

Schloss Leopoldskron, Salzburg, Austria

Schloss Leopoldskron, Salzburg, Austria

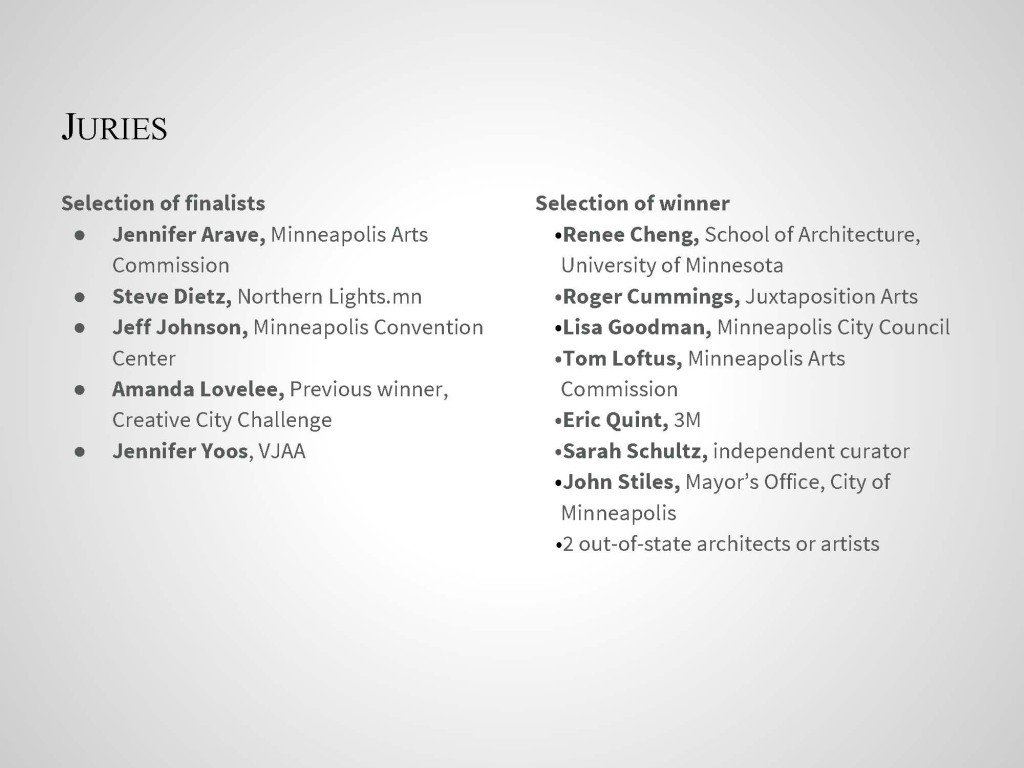

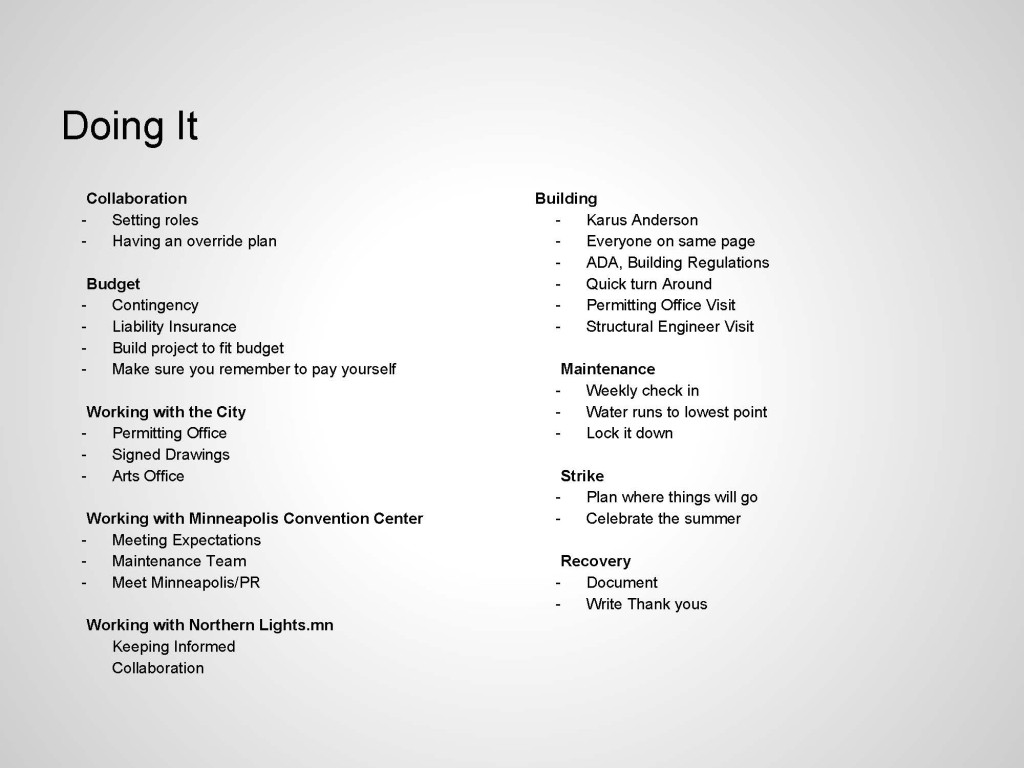

Info session: Wednesday, November 5, 6 pm, Room 102F, Minneapolis Convention Center https://www.facebook.com/events/599060416882776/

Info session: Wednesday, November 5, 6 pm, Room 102F, Minneapolis Convention Center https://www.facebook.com/events/599060416882776/