This article originally appeared in the catalog for the Greater Minneapolis 08 show at the Soap Factory this fall. Curated by Patty Healy McMeans and Christopher Dela Pole, the exhibit showcased the work of 22 Minneapolis-based artists. The six artists discussed here each practice a form of public and/or performative artmaking.

Public/Private

Theorist Sven Lutticken writes that the role of the contemporary artist is one of “permanent public self-performance.” This intimidating endgame isn’t reserved only for artists, though; Lutticken further argues that all of us, in one role or another, so long as it’s a role played in our service economy, exist under pressures of a “merciless economic drive to perform,” to bring our personalities into play in our every interaction, to “make it personal.” No matter what our role, no matter what we’re paid.

This fundamental invasion of privacy begs the question: who are our private selves? Where are they allowed to exist and develop, if in so many moments we are expected – and expect ourselves – to “act”? The self can get lost in its own publicity.

When we think about issues that crystallize contemporary dynamics between public and private life, we might first think of, say, surveillance of our private records and activities in semi-public realms like the Internet, your credit card company’s databases, or the halls of government. Perhaps most often, we think of the distinction between public and private in terms of the visible and the invisible. We think of the public self as the self seen by others, consciously shown to others, and of the private self as the one we might be able to hide – the self with bad habits, the self of the inner monologue, or the self who, rather than performing, can just “be.” The word “public” also calls to mind networks and structures, institutions, macro-level politics and “the big picture.” These concepts usually have their pairs in the private sphere – thus, we have public parks and private yards; institutional buildings and homes; religion and religious belief; parades and diaries. But people conduct their private lives in public parks – and at all times, everywhere. In fact, you can’t actually stop enacting you private self, anywhere, ever. Assembly and solitude each contain the one and the multitude. The conventional public/private dichotomy thus breaks down.

Many of the artists in Pay Attention: GM08 make work from a standpoint that acknowledges we cannot avoid this constant self-performance; at the same time, their work encourages us to consider that we are potential performers of ideas and selves we’ve yet to enact or imagine. These artists concern themselves with an examination of behavior via performance and the creation of performative circumstances. Many perform their own work, and some include accomplices; others do not perform their work but, instead, lay the foundation for work that’s only completed through the viewer’s witting or unwitting participation. Still others capture and comment on the kinds of performances enacted daily by all of us, producing not new behaviors but reflections on our current ones.

Performance and performative artworks often enact incursions of “private” behavior in the “public” realm. Seeing someone risk their reputation in public by doing something considered “private” can have profound effects on the viewer; we share a basic need to witness another’s life (so that we may affirm our own), to identify with another. But beyond addressing the requirements of catharsis and identification, contemporary performative artworks often showcase how things “public” and “private” are not locked in opposition to each other but, rather, exist on a continuum. A dynamic opposition can exist between public and private (ever stand next to your window, naked?), but the actions we assign to each of these categories can also be made to trade places, and to great effect.

The artists in GM08 engage us in the performative process, making public – and obvious – the quotidian habits, situations, and constructs of the life lived along this public/private continuum that often go unnoticed. Providing the context for thought, action, and interaction, these works often invite our co-authorship: we are instrumental in making this art be art at all.

Marcus Young

Marcus Young’s trio of public actions for this show, entitled collectively “This is Not Here,” takes place in real time and in public spaces that are not within the Soap Factory itself. These performances are made for those who happen to be there, witnessing as would people who hear trees falling in the woods; they are complicit in that experience, and so it happens.

In one solo work, Young smiles continuously while walking very slowly in a public space – in this case, an art institution’s exhibition halls. This deceptively simple act tweaks our presumptions about what kinds of behavior are “appropriate” in public: slow walking can interrupt the flow of foot-traffic (bad), draw attention to you (also bad), and may indicate that you’re not feeling well (a plea for help?). But pairing it with smiling turns the walk into what appears to be a vivid expression of the “private” self – it reads as a spiritual exercise. We soon realize we want the smile to be an expression of an inner state, making this long walk (long in time, if not in space) meaningful, if still utterly inscrutable. Again, our desire makes us complicit in the performance. The artist may experience this as an act of endurance, but we want this to be a gesture of human freedom, a willful inscription of the private on public territory.

In another work, which he refers to as “Theater for the Ear,” Young and his cohorts approach unwitting strangers and whisper in their ears. The text whispered addresses the listener directly; the impropriety of being whispered to by a stranger in a public place only heightens the excitement inspired by this direct address. Whatever else is said, the form of address alone stuns the listener with its refusal to abide by social convention.

These acts transform their institutional sites from spaces of benign reception and contemplation into dynamic, interactive zones where questions can be leveled directly at the audience. Bodily participation is required by these pieces, as opposed to mere scopophilia; we comprehend that meanings are made between things, between ourselves and the work, rather than by the things themselves. This necessarily makes us aware of our co-production of meaning.

For Young’s piece “Don’t you feel it too?”, a dance happening recurrently in public spaces for GM08 and premiering during the Republican National Convention, the call for performers says, “the only qualification is a willingness to say hello to your personal awkwardness and accompanying happiness,” as well as promising the kind of joy that can only accompany “nonstandardized behavior.” The expectations of Young’s work may make us self-conscious to begin with, but also self-reflexive, more aware of our own thresholds, expectations – and options. His work produces a context for witnessing and acknowledgement that extends beyond the usual expectations of the spectacle – our internal, private monologues about the work and how we’re allowing ourselves to interact with it become part of the work itself.

Julia Kouneski

Julia Kouneski’s work also encourages unusual and delicate interactions between humans, often with a mechanized intermediary. Having worked with the breath using motion sensors in the past, she now engages collective breath with her two-person balloons. Altered to have two valves each, these balloons can and must be shared with others in order to inflate properly. She herself has asked strangers to share them with her, documenting the results, and throughout GM08, the balloons are being given away to visitors at the gallery entrance. These strange objects present the recipient with multiple questions and options: First, what is this? And what will I do with it? Am I brave enough to try it? Will I use it here, or somewhere else? With a friend? A stranger? Once you decide to try it, more options emerge for its specific use: to share one breath and allow it to deflate, a momentary communal lung? Or to share it to the point of inflating it completely and tying it off, saving the breath to fashion it semi-permanently? Either outcome is possible, but it’s the experience of vulnerability and shared effort that is most affecting. In making what could be called an “emergent object,” Kouneski has created an object that, as we fondle it, makes us nervous with possibility.

In performative works, there is often a call to join in – an expectation that you, too, will perform beyond your normal range. Kouneski’s requests for your participation put your private self on the spot in public – how will you react? Will you do what’s requested of you? And then what? Although overt performative expectations of the viewer – to participate in a work and make an artist’s plastic initiatives come alive – can be exhausting, and can create determined resistance in an audience who would rather keep its reactions to itself, full participants may be rewarded for their responsiveness and instrumentality; being asked, essentially, to come out and play, disarming as that is, is nothing if not exciting, and it’s not every day you get to blow a balloon with a stranger.

Tony Sunder

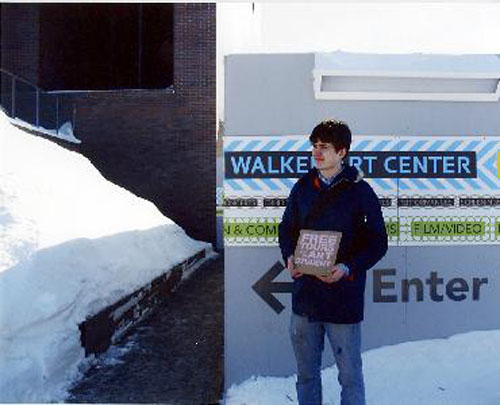

Tony Sunder for a time conducted free tours at the Walker Art Center for anyone who took him up on his offer. He had never been and was not at the time employed by or affiliated with the Walker. This performed standing-in for the institutional voice put his followers’ trust of the institution on the line, highlighting both their need to put their knowledge in the hands of an external voice and their willingness to play with other perspectives by allowing a man off the street to conduct them through the museum. For this show, he has hand-crafted gallery benches and placed them himself around the Soap Factory in relation to other artworks. Their placement in front of certain works (and not others) indicates what we are meant to contemplate most deeply. Will you take the familiar hint, sit down and spend time with what the bench angles your attention toward? Or will you notice the power play involved, and choose not to sit at all? By interacting bodily, even performatively, with these benches, you become accountable for your private experience of accepting – or not – the pre-conceived valuations their physical placement connotes.

The full intentions of Sunder’s works – performances and objects alike – fly beneath the radar, but sly as they are, they create an acute awareness in the observer that you must, in relation to these works (and, by extension, every work of art you see), choose either to refuse its invitation, or to submit to it. As interactive stratagems, they make you aware of the power inherent in where you choose to direct your attention.

Jonathan Gomez Whitney

Jonathan Gomez Whitney’s sleight-of-hand installations, in which he both performs and invites others to perform, are rarely what they first seem. Take, for instance, his weekly poker game set up in a Soap Factory storage room for the duration of the show. Word-of-mouth is the only publicity for the game and its enlistment of players, and this alone generates public interest. Poker playing is a normative behavior, but playing it in a semi-secretly released room in the public space of an art gallery takes the game that’s normally played in a home, bar, or casino, and makes of its behaviors something else. Are we no longer just playing poker? Are we now “performing” poker? The set-up allows for several observers, as well, so now there’s an audience to watch, to see the players’ hands. Perhaps nothing better defines the tension between public and private than the concept of an “open secret,” and an open secret is just what Gomez Whitney has created, functionally and experientially. It’s an engagement of the public, but one that’s stealthy, and privately accomplished.

Gomez Whitney further feigns a full invitation by setting up an altered, amplified organ in the space of the gallery. It looks inviting, but if you played it (and you’re not allowed to), the sounds that come out would not be standard ones. Jonathan engages in physics experiments on musical instruments that result more in poetic meaning than harmonic sound. He performs a song with the organ on opening night about broken-up friendships, and what remains afterward is, yes, the organ itself – but also, drawn out as long as is technically possible, its post-performance hum. The ongoing buzz of the instrument is a reminder of the object’s energetic performance potential, but more importantly of the energetic hum stemming from all the potential performances awaiting our enactment.

Ali Momeni

Ali Momeni produces much of his work in the public sphere, creating machines and interactive systems that allow for evanescent, experiential art making. His work often animates public space through large-scale projections that embrace elements of chance. He currently heads a team of artists called Minneapolis Art on Wheels, a mobile art project wherein bikes equipped with a high-powered projector, laptop, sound system, and power source can project art wherever the bikes can be ridden. The projected content, often created live and in real time by artist-built computer programs, is frequently co-created by the random audience accumulating around the bikes.

Momeni’s interest in “emergent behaviors” – behaviors that arise from the entirety of a system that could not arise from its individual parts – leads him to experiment with system-building on both material and immaterial, even social levels. He has created projections in which tiny movements made by his fingers create and control the movements of large-scale visual phenomena; he also built a sculptural installation where the experimental movements made by a person encased in a giant joystick ultimately, through computer synthesis of the joystick’s movements, created club-worthy dance music. These works of translation from intuitive, self-directed physical movement to technically advanced aesthetic output are at the same time translating the performance of private-scale, individual acts into socially-participatory phenomena, enlarging the dynamic range of individual actions in the public sphere. In all of these projects, by setting up a system and seeing what it does – and what people do in response to it – Momeni makes space for new possibilities for social and aesthetic action, and for performances that surprise artist and audience alike.

Chris Baker

Much of Chris Baker’s work holds a mirror to our most mundane performative practices, and in it we contemplate their pathos. Most of his works for this show focus on the confessional, exhibitionistic habits of online bloggers and vloggers. In the piece entitled “It’s been awhile since I last wrote…,” a single LED traces the title sentence, in apparently handwritten script, across a photoluminescent wall, then fades – a process that repeats, again and again. For anyone writing this sentence online (and many have), there’s a technological pathetic fallacy at work; it requires imagining that there is a “community” beyond and because of the blog. Simply because we’ve trained a camera on ourselves or opened a public diary, we begin to imagine ourselves the subject of careful surveillance. The script’s fade to invisibility reinforces how little impact this level of private visibility makes on any larger public fact. But its endless return signals the inevitability of our basic need to be heard. Even those who’ve only written such a line in a private journal feel a twinge of recognition; as Baker points out, the sentence calls to mind both the need to be attended to by others and the estrangement (from the moment and from others) that’s inherent to writing and to communication in general.

In his work “Hello World! or: How I Learned to Stop Listening and Love the Noise,” one confronts a massive projection of thousands of youtube videos of people vlogging, alone, staring into the camera and externalizing their inner monologue. Its title refers to the utopic fantasy inherent to technological advancement (“Hello World!” is the name of the first program computer science students learn to build) as well as to the utopic desire inherent in posting one’s “self” on youtube. Baker aimed to choose first-timers – those with low production values who volunteer a lot of personal information (some of which can be made out in the 30-track audio for the piece). They seem lost, looking down from the camera every two or three seconds to see themselves on their own computer screen in a circular, self-referential gaze – and it takes them awhile to figure out how to present themselves; we literally watch them get their “act” together. These individuals seem both hyper-aware of themselves and totally un-self-conscious, fidgeting while releasing stream-of-consciousness narration. Taking it all in, we move from empathy to estrangement, because finally, there is an irresolvable vastness of content to this much-multiplied self-presentation. For vloggers, there is no interaction with an actual listener, only with an imagined receiver, and the seemingly infinite number of potential human connections to which the piece refers remain, at best, potential.

At first glance, Baker’s works seem to lampoon the narcissism and futility of contemporary technological gestures toward interconnection, deflating their apparent arrogance and naivete. But, as the owner of the hand that writes the fading, recurrent sentence, he too, he seems to admit, performs his “self” – as have any of us who’ve ever recorded our thoughts in first-person.

Much as the many and multiplying international art fairs serve to illustrate broader cultural trends at any given moment, the Olympic Games, occurring as they do every four years and produced as a televised spectacle, can act as a barometer of current cultural practices and norms. This year, there were the usual unscripted interactions between athletes and coaches, reporters grilling athletes post-competition, and pre-recorded bio videos between events to tell athletes’ personal stories. But the moment that seemed most indicative of our current collapse of private and public life was the moment we got to listen in on the US Womens’ gymnastics team huddling to talk strategy. They were surrounded not by reporters but by multiple cameras, all of which lingered on them, without voice-over or analysis from on-air commentators, for the length of their conversation. The gymnasts seemed not annoyed by but actually prepared for this, fully accepting of and ready for it. It was as if the cameras weren’t even there. Or, perhaps more startling, it was as if they were there.

Such performance of the self is nothing new in the era of “reality” television, youtube, Facebook, and all the other players in the genre of technological self-promotion. The task of the artist, in a world where such media incursions are the norm, may be to continue to sort out our options for participation and action beyond the spectacular.

Even in moments of public self-performance, there is a fundamental exchange between the performed self and the private self who monitors what gets said and what doesn’t, what’s shown and what isn’t. The performative artworks in GM08 challenge the private self; even when they request a more public response, they offer an opportunity for development – even for engaged argument – to the private self, the self whose existence no market can dictate but who all sorts of markets would like to exploit. Art that enacts unusual behaviors, asks unusual behaviors of us, or that recontextualizes our seemingly mundane behaviors makes room for us to consider that we may, in fact, want something more from ourselves than we’re presently accomplishing. And sometimes, the immediate rewards of opening ourselves to experience these behavioral works can open the door to that self-revision.

Sarah Petersen is a multidisciplinary artist living in Minneapolis