“At a basic level, City Fight! is an experiment in making cities into playthings.”

City Flight

My work emerges from the recombination of ideas from architecture, software development, biology, physics, social sciences, and other domains. I am educated as an architect and identify primarily with the discipline of architecture, but my medium is software. The software applications I create are tools that allow people to playfully engage with the creative process of design. They incorporate techniques from video games, the sciences, and social media to arrive at novel 3D design tools that act as a counterpoint to traditional design software. I am exploring techniques from multiplayer/networked video games, biological growth processes, machine learning, social software, and crowdsourcing to build creative, participatory design tools.

City Fight! is a video game that involves two players standing side by side facing a large screen. On the screen are two city grids (one red, one blue) separated by a river. Each player’s goal is to build a complete city before his or her opponent does. At each turn a skyscraper, an apartment block, a park, or another piece of a city is launched upward into view of the players. These pieces are colored red or blue, indicating which player needs that piece. The two opponents fight to determine where it will land by using their arms to hit it in the direction of their grid. Once a piece is hit, it falls onto the city grid and sprouts into the Empire State Building, the Eiffel Tower, the Great Pyramids, or another of hundreds of buildings and landmarks from around the world.

Turn by turn, both grids fill with an eclectic assortment of structures, each city forming a unique but oddly familiar assemblage of international architecture. Each player sees an indicator showing the completeness of their city; it notes whether a city needs more tall buildings, more housing, more open space, or other necessary components. Players can sabotage each other by stealing pieces before the opponent can hit them. This theft might help a city, but it could also overcrowd it with shopping malls or parking garages. A bomb launches periodically, giving players the opportunity to blow up part of the opponent’s city or get rid of unnecessary parts of their own. Eventually either red or blue will win by hitting one final piece into place. The winner is treated to an aerial tour of their new city.

At a basic level, City Fight! is an experiment in making cities into playthings. By building in a fast, fun, and humorous way, the seemingly static cities we inhabit may become more flexible and dynamic in our minds.

City Fight! is also about the growth of modern cities. This process is a continual struggle between political, social, and commercial interests that can feel at times random, bewildering, or wonderful. The game creates an environment in which those same emotions can be felt, often in rapid succession. By experiencing the growth of a city in fast-forward, this process can be illuminated in all its messiness, complexity, and absurdity.

Background

Art is relational and interactive, because it is designed to be viewed and is meant to inspire a response. When artists began to use computer software as an aesthetic medium, the relational and interactive possibilities for art expanded. Until recently, interactive computer-based art presented viewers with a keyboard, mouse, or sensing devices that could do little more than mirror the viewer’s image with patterns on a screen. Everything changed with the invention of powerful “gestural interfaces” that now allow viewers to control complex computer functions with the wave of a hand. Artist Aaron Westre uses Microsoft’s popular Kinect controller (one of the most well known gestural interfaces that is the motion-sensing input device for the Xbox 360 video game console) to power City Fight!, his interactive installation on the theme of urban development.

When two viewers stand with hands raised in front of Westre’s installation, the Kinect controller recognizes their skeletal structures and begins to map their hand movements onto game paddles within a gridded game board projected on a large screen. Even though gestural interfaces such as the Xbox and Nintendo’s Wii are only a few years old, we already know how to plug our bodies into these wireless computer technologies, and we enjoy seeing our movements translated into projected spectacles.

The game begins as soon as Westre’s software couples with participants’ bodies. Balls shoot onto the board and land as valuable urban property. Knock a property to your side of the board and your city grows and thrives; lose it to your opponent and weep at your diminished symbolic wealth and prestige. Players throw themselves into the action, slapping, whacking, swatting, and grunting as they maneuver for properties, their actions amplified by loud thumps that sound as game pieces are launched and then land. Of course, no game about urban development would be complete without the opportunity to steal your opponent’s property or the occasional destructive blast of terrorist attack or gas main failure. City Fight! has them all.

Westre set up two screens: one gives a bird’s-eye view of the virtual action, the other runs tight shots of properties as they land on the urban parcels marked on the board. This dynamic presentation of the competition attracts and entertains the audiences that gather to watch the play.

City Fight! is a fun game with a serious message: the business of urban development is messy, chaotic, reactive, and cutthroat. Politicians, special interest groups, and wealthy developers mobilize the capital behind urban building projects and manipulate city governments to write and rewrite zoning codes. Populations are displaced, businesses prosper or are ruined, histories are buried, and fortunes and political campaigns are won and lost in the real game of urban development in the cities where we live.

Artist Statement

My work emerges from the recombination of ideas from architecture, software development, biology, physics, social sciences, and other domains. I am educated as an architect and identify primarily with the discipline of architecture, but my medium is software. The software applications I create are tools that allow people to playfully engage with the creative process of architectural design. They incorporate techniques from video games, the sciences, and social media to arrive at novel 3D design tools that act as a counterpoint to more traditional design software. I am currently exploring techniques from multiplayer/networked video games, biological growth processes, machine learning, social software, and crowdsourcing to build creative, participatory design tools.

Biography

b. 1975, Willmar, Minnesota

works St. Paul

mentor:

Aaron Westre is a software developer working at the intersection of science, art, and design. He received a Master of Architecture degree from the University of Minnesota in 2008 and is now an instructor at the University of Minnesota School of Architecture, where he teaches students how to create digital tools. His research and creative interests lie in building software that allows artists and designers to expand their capacity to create, communicate, and collaborate.

Links

Drew Anderson, Near the Ghosts of Sugarloaf

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“Art’s aspiration to link human consciousness with technology is still alive and well.”

Near the Ghosts of Sugarloaf

Technology as a creative medium has led me to the threshold of a miniature world, inhabited by small cameras, projectors, and puppets. I cannot claim to be a bona fide puppeteer, but I am making inroads in mechanical, miniature theater. With analog and digital technology I orchestrate tiny robotic figures, or automatons, and mix in other visual and interactive elements, such as projections and biomedical technology. Heart-rate sensors allow me to capture the human pulse digitally and render the digital into another form, such as mechanized motion or light. I’m interested in the displacement of the heartbeat outside the body and the experience of the real and artificial pulsing together.

My projection work stems from my collaborations with the collective Minneapolis Art on Wheels, whose outdoor projections range from large-scale drawings displayed on buildings to tiny animations beamed on sidewalks. Mobility is important to MAW and recently inspired the creation of a handheld, portable projector.

A similar device plays a pivotal role in my latest work, Near the Ghosts of Sugarloaf. This piece draws from my experiences deer hunting in northern Minnesota and deploys a miniature automaton and landscape in the likeness of a deer hunter and boreal forest. What the puppet hunter sees via a small camera attached to its head is broadcast live to a pulse-sensitive portable projector. Viewers may wander throughout the Soap Factory with this device in search of projection surfaces. In the projected image, participants see the miniature landscape through the eye of the puppet. Through the “eyes of the projection,” they intimately experience the hunt modulated by the rhythm of their pulse captured through the stock of the projection device.

The miniature realm is appropriate for my relatively small and remote world of hunting. It deals first with the divide between my personal activity as a hunter and the emotions I intend to convey. Accuracy is obviously impossible, especially in an urban environment like the Soap Factory, yet my miniature theater deliberately owns that irony and exploits it in a way unique to puppetry. The work’s playful abstraction of my subject relays a mood true to the forest in which I hunt and conjures the spirit of the hunt. Puppetry and technology allow the story to unfold as both an artificial reality and an evocative experience. I want to continue mixing technology and traditional art forms as open tools for telling stories in a new form.

Background

Does technology bring us closer to nature, or does it distance us from it? Drew Anderson’s Near the Ghosts of Sugarloaf asks viewers to ponder this question.

Anderson’s most powerful memories are drawn from family hunting trips “up north” in woods around Floodwood, Minnesota, northwest of Duluth. Alone in the woods, taking in the smells of the earth, he says, “you can hear every footstep, the wind, your own heart beating.” Anderson’s life in the city could not be more different. A lasercutting technician by day, he is a member of the Minneapolis Art on Wheels new-media artists collective by night. In this collective he works with computer and video technology to produce public art that is projected on the sides of buildings through the city with the aim of prompting public discussion about issues that matter—or just to have fun.

Anderson’s two worlds collide in Near the Ghosts of Sugarloaf, which is a puppet theater, landscape panorama (made of branches and twigs gathered from the forest around Floodwood), and a viewing and projection machine designed to share the artist’s experience of hunting with his viewers. Suspended in the middle of the unheated, industrial outer gallery of the Soap Factory, this satellite-like orb is a platform stage for a mechanical hunter-puppet with a camera for eyes. This diminutive mechanical automaton is an unlikely artistic medium for sharing profound personal experiences, but it leads in that direction. It is a mechanical art interface that entwines perceptions and attempts to merge human consciousness.

Holding a little rifle in its mechanical hands, the puppet is the artist’s surrogate self as a hunter roaming the forest. The viewer/participant mirrors the puppet when he or she takes hold of the installation’s rifle accessory, which vibrates as its sensors register the user’s beating heart. The rifle accessory becomes a mobile projector that throws incoming images from the puppet’s eyes onto the dilapidated gallery walls, all the while emitting the sound of steps crushing leaves underfoot. With rifle accessory in hand, heartbeat pulsating, and forest scenes dancing on the walls of the rough, chilly gallery interior, the perceptions of the participant and the puppet overlap and merge; momentarily coupled, together they are a wandering, sensing, hunting machine. Art’s aspiration to link human consciousness with technology is still alive and well.

Artist Statement

My art explores human stress that is both psychological and physical. I often use the concepts of time and rhythm to embody human emotion. The perception of time as an opposing force intrigues me, because in a deadline, routine, or test, the obstacle is time. I also admire the rhythm of the body when it undertakes a time-controlled task. Whether that task is manual labor or preparing a meal, an aspect of repetition and a sense of pace are involved. Video installation, kinetic sculpture, and interactive technology are my primary mediums, and over the past two years, I have explored how to cross these mediums and best represent my subject.

Biography

b. 1988, Duluth

works Minneapolis

mentor: Christopher Baker

Drew Anderson grew up in Cloquet, Minnesota. He studied English, music, and art at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities and graduated in 2010 with an individually designed degree. He is a research assistant for artists Ali Momeni and Jenny Schmid and has participated in several of their works, including Momeni and Schmid’s Battle of Everyouth in the 2011 Northern Spark Festival, Minneapolis; Schmid’s VLD SK8R GRL, 2011, Istanbul, Turkey; and Momeni and Schmid’s Department of Smoke and Mirrors, 2012, Wellesley, Massachusetts. He lives in Minneapolis, where he is an active member of the Minneapolis Art on Wheels collective and works as a laser-cutter technician for the University of Minnesota’s Department of Art.

Links

Anthony Tran, Wire less

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“Today, our bodies are the sites of endless reception and transmission of wireless communication, which produces new currents of radiation flow around and through our bodies.”

Project Statement

Wire less is a visualization and exploration of electromagnetic space and its effects on identity and the body.

Humans naturally give off electromagnetic radiation, but as we store more digital information on us through technologies such as cell phones and laptops, that radiation grows exponentially and in complexity. These wireless emitting devices are not only communication tools but also sensors of the invisible electromagnetic environment that surrounds us. They make us aware of what is called Hertzian space, the cloud of electromagnetic radiation that is always around us. This space not only envelops our body; our body is a mediator of it. Our neurological synapses intertwine with the data we transmit.

With increased use of wireless technologies to interface between humans, we sift our bodies through this electromagnetic space, exposing, disassembling, and dispersing our identities to the open air. We text message through unencrypted networks, browse Facebook under corporate surveillance, and curate pictures for peers to interpret us. As we leave these fragmented traces, others then compile and reinterpret them as our imaginary present.

Utilizing 3D body tracking and ambient radio frequency sensors, Wire less deals with the state of our bodies in a saturated world of overlapping and scrambled signals that we sense but cannot see. Wire less seeks to make these invisible signals visible. This leads to a new cartography where the merging of our projected, virtual selves now coincides with our physical, current selves. We no longer look at the screen and see a digital echo, a modern mirror image of us; rather, we have become a version of Narcissus that has fallen into a sea of self-created reflections. Our bodies remain but are engulfed in distorted radiation.

TITLE TBD – Patricia Briggs

All life is linked by electromagnetic activity, yet most of this action takes place outside the spectrum detectable by human sensation. Although we see the light and feel the warmth that the sun radiates, we don’t see or feel the enormous solar blasts that throw waves of electromagnetically charged particles into the earth’s atmosphere—but our wireless devices do. Whole city power grids can be knocked out by solar eruptions, which cause radio wave blackouts, satellite and airport navigation system malfunctions, and heightened northern lights auroras.

Our relationship to electronics influences our relationship to electromagnetic fields. In the electronics age, our ability to manipulate electromagnetic currents restructured culture. Power grids began to shape city plans, and almost every activity came to be organized around the availability of electrical outlets. Rechargeable batteries and wireless technologies liberated us from the wired grid and made our interaction with electronic devices more ubiquitous and increasingly intimate. Today, our bodies are the sites of endless reception and transmission of wireless communication, which produces new currents of radiation flow around and through our bodies. Artist Anthony Tran was born and raised in the hyperconnected environment of wireless digital technology, and he rejects the division of the world into animate and inanimate objects, organic and inorganic matter, nature and machines. Instead he explores the dynamic field of radiation and electromagnetic current that links men and women to their smartphones, GPS devices, iPads, laptops, game systems, RFID tags, and more.

In Wire less, Tran defamiliarizes the real by manipulating the rules of vision. The viewer enters this installation in complete darkness, but Tran’s technology reads the viewer’s presence, maps the body, and uses it, in turn, as a screen for its transmission of a projected pattern of light. Mapped by 3D sensing software, this projection clings to the viewer’s body like a transmission successfully received. In moments of illumination, the viewer catches glimpses of his or her body lit by these pattern transmissions in large mirrors placed at one end of the gallery.

When the sensors in Tran’s installation machines register heightened levels of radiation–electromagnetic activity (usually emanated by personal electronic devices), they generate a new picture that maps the viewer’s silhouette in red and purple light. These colors exist at the edge of human perception and represent currents of invisible radiation circulating around and through the body. Tran’s software configures a pattern of fluid movement that is projected toward the viewer’s body but not onto it. Again, catching the mirror’s reflection, the viewer sees an aurora of light glowing around the darkened shape of his or her body. Tran’s installation shows the human body at the center of an eclipse representing the radiation generated from the body by the electronic devices that gravitate around it.

Artist Statement

I am passionate about science and art. The blurring of the two domains pervades the modern world, as it increasingly becomes more collaborative and connected. Contemporary digital art inherently mingles with art & science as well as the reinvention of the present to create the future. My work delves into the feedback loop that occurs between machine and man. Through creating spaces that are neither completely virtual nor fully real, I attempt to extend reality into a space that is transitional. I believe that this is representative of our time as there is still a gap between human consciousness and computer logic. Through making this explicit, I hope to lessen this gap and thus progress this transition, while realizing that it is the problemitization of the past and present that informs this future.

Biography

b. 1989, New York, New York

works St. Paul

mentor: Christopher Baker

As a new media artist, researcher, and technologist, I create temporary spaces to expose the relationship between technologies and the extrasensory mythologies they produce, and I reappropriate recently mass-adopted technologies to subvert their persuasive notions of security and reliance. We live in a society obsessed with the “new,” and we often let our guard down to embrace the so-called promise of the future. I seek to bring a hyperawareness of the present through modern cultural artifacts—to bring heightened awareness to a very externally focused world.

Links

Mike Hoyt, Poho Posit

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“Hoyt’s Poho Posit … celebrates the community connectivity offered by the online forum and works to establish a role for artists in this emerging digital territory.”

Poho Posit

My south Minneapolis neighborhood is full of active, civically engaged residents; an assemblage of attentive eyes and ears. Every day, via a 846-member online forum, people report and discuss a multitude of things that happen in and around the neighborhood: a string of garage break-ins, a lost turtle, gang graffiti, a formerly-missing tabby named “Fozner,” now found, the attempted abduction of a minor, free sheetrock and shelving units, gun shots echoing through dark alleys, group yoga instruction in a park, and a garage sale!

Because this is the community in which I live and work, the forum topics have fueled my curiosity and enticed me to participate in some way. I was lured to the specific locations mentioned in the posts because I wanted to “see” and experience where these events were happening. This survey has led me to create an ongoing series of hand-painted stop motion videos of specific events gleaned from the online forum.

Creating video-paintings and posting them on the online forum has become a way for me to internalize and process the information I gather online and at each physical location, as well as to participate in the community dialogue as a neighbor and artist. The video-paintings are a re-presentation of the reported events. They posit a visual sequence of accounts that exists somewhere between reported facts and fabrications. They add to the broader community dialogue by elevating everyday occurrences through beauty and a meditated response that, in turn, introduces a divergent vernacular.

Over the past decade, my work has evolved to take on the form of sound and/or sculptural installations and situations in which public participation is a key component. This project brings me back to my roots as a painter, while challenging me to incorporate new media and digital technology. I am captivated by the possibilities of merging a pre-industrial craft (painting) with networked digital technologies (coding). Introducing “slow media” into a hyper media world obliterates the fleeting nature of an online forum, and stretches the timeline for discussion and rumination.

This project has developed as an ongoing creative endeavor that will span several years. It is exhibited simultaneously in several interdependent formats: as a physical installation which incorporates an interactive map kiosk, as the website www.pohoposit.com, and as visible markers posted throughout the neighborhood at locations portrayed in the video-paintings.

Patricia Briggs

There was a time when neighborhood news traveled from person to person by word of mouth. Neighbors shared points of pressing information by talking across backyard fences or dialing one another in the order designated by a carefully crafted telephone tree. News of a car break-in or the sighting of an unfamiliar face rippled down the streets from house to house slowly over the course of hours or, more likely, days. Now, in urban neighborhoods like Minneapolis’s Powderhorn Park where artist Mike Hoyt lives, safety-conscious, digitally savvy citizens share news instantaneously through e-democracy online discussion forums. Neighborhood anomalies are no longer subject to the spatial–temporal limitations of the spoken word but are immediately reported online: “Keep your eyes open: burglar spotted at 31st and Bloomington! Description: Male Caucasian—6 feet 2 inches.” “Someone took my garbage container from the alley behind my house.” “Our home was vandalized this evening shortly before 8:00.” One neighbor’s experience is instantly communicated to all. With the eyes of everyone in the neighborhood linked in surveillance via the web, there are few quiet news days.

Neighborhood web surveillance may call to mind images of frightened citizens ready at all times to dial 911, eyes glued to live video fed from cameras mounted outside their homes. Some artists have addressed this issue by representing video surveillance as a way for the police to identify and eradicate undesirables like illegal vendors, activists, and street people from public squares and parks. Hoyt’s Poho Posit instead celebrates the community connectivity offered by the online forum and works to establish a role for artists in this emerging digital territory.

Poho Posit is an interactive portrait of Powderhorn Park that aims to be as participatory and interactive as the discussion forum it is based on. Acting like a crime scene investigator, Hoyt visits the alleys, bus stops, and street intersections he has read about in posts. He takes photographs, then renders the reported events as he imagines they would have appeared: chickens loose in an alley in the middle of the night, strangers in a parking lot trying to open car doors, an intruder making his way up the stairs of an apartment building. He represents these scenes in a beautiful Hopperesque style, then turns his drawings into animated video micronarratives that he posts on the web. At the actual locations of the original reports he posts inconspicuous signs with QR codes that link his neighbors’ smartphones directly to his animations, embedded in a gorgeous hand-drawn map that includes every tightly plotted lot in Powderhorn Park. The original drawings for this map are arranged as an installation in the Soap Factory gallery, and neighborhood residents are invited to take the framed sections representing plots where they live. Hoyt recognizes the poetry and the beauty in the banal realities of urban living narrated in his neighbors’ daily posts. With Poho Posit he lovingly re-creates them and gives them back to the community as gifts.

Artist Statement

I seek to establish new and unique creative methodologies that push boundaries for what, why, and how art engages diverse public participants. I seek challenges to examine art and the social role of artists as well as being a vehicle for aesthetic representation. In the past decade, my work has taken on the form of environments, installations and situations that invite the public to freely participate, when presented. Although I earned a BFA in drawing and painting, I attribute this tendency to my previous work as a theatrical set designer. I am driven by the possibilities of simultaneously producing art objects, creating a platform for facilitating unique shared experience, and connecting diverse and often nontraditional art audiences.

Biography

b. 1970, Northfield, Minnesota

works Minneapolis

mentor: Wing Young Huie

For nearly twenty years I have worked as an artist in two distinct modes. One is creating art objects and public art projects and exhibiting them in conventional arts and cultural venues. The other involves designing, implementing, and embedding arts-integrated youth development programs in nontraditional arts institutions. These have included neighborhood development programs, homeless youth drop-in centers, youth employment programs, and nonprofit social service agencies.

I have been fortunate to exhibit artwork and produce public art across a wide range of communities and venues. Reaching new audiences in unexpected ways through art is important to me. Whether I’m working with a gathering of ice fishers in the suburban Midwest, tourists in Waikiki, financial executives on their lunch break, rural Minnesotans, or Twin Cities homeless youth, I believe my work is most successful when it actively engages diverse groups of people in meaningful creative exchange.

Links

Caly McMorrow, Status Update

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“By the time the last word in a sentence is spoken, the first has already been lost.”

Status Update

I find interest where lines blur between artistic disciplines, techniques, genres, and ideas, and I enjoy exploring relationships between seemingly disparate elements. I’m inspired by the juxtaposition and merging of old with new; live with automatic; organic with electronic; and creator with audience. Common themes in my work are the mutable nature of memory and history, and alternate versions of the past, present, and future. I’m influenced by aesthetics of retrofuturism and science fiction.

My new body of work includes installations incorporating sound, light, interactivity, and indeterminacy based on participant input. Something—a light or sound or activity—changes with the intervention of audience members. Interactive work challenges the assumptions that art is to be seen and not touched and that technology, art, and creation are inaccessible or reserved for an elite.

Status Update explores communication and the simultaneously cyclical, mutable, and ephemeral nature of time and memory. Audience participants are invited to move through a spiral of spoken recordings and vintage lights. Using an antique phone, they may record an answer to a question for the next participants to hear. Sound and light move together through the spiral, and as older recordings progress through, new thoughts begin the same journey from the center outward.

The illumination of a lightbulb is often associated with new thoughts, ideas, or revelations. Thoughts and ideas become words, and words become record. Any form of record can capture these singular moments that would otherwise be more ephemeral, but often a record can be easily overwritten, destroyed, forgotten, or misinterpreted. In this installation, recorded responses are collected, separated from their questions, possibly repeated, possibly discarded, and open to the interpretations of those listening.

These recordings originate from an antique telephone, a physical representation and reminder of how technological advances have changed immensely yet still fulfill our basic desire to share information and stay connected. Status Update asks its participants to use an antique to record a thought that will soon be mostly lost to history and its interpretations. New ideas become technological advancement and innovation, but they are always linked to what came before.

Patricia Briggs

Status Update is a sound and light installation inspired by Facebook, where informal written communication takes on the collaborative character of spoken language, as “status updates” constantly mark time by pushing earlier posts further down the page. A new textual practice has emerged as users follow the prompt “what’s on your mind” and contribute posts to the unending, collectively written text. The functions served by this new writing practice and its impact on its users’ subjectivity comprise new fields of linguistic and philosophical study, while Facebook offers a new generation of artists fodder for reflection on the nature of language and the status of the spoken word.

In this age of constantly updated social media, what is the difference between the written and spoken word? Speaking preceded writing in the development of human communication just as it does in child development. Philosophers often link human consciousness with the spoken word, which seems, more than writing, authentically from the self. Spoken communications have intonation, inflection, volume, pitch, and pulse, and unlike written texts, which are the products of more cautious deliberation, they are invisible and ephemeral. By the time the last word in a sentence is spoken, the first has already been lost. Yet these ephemeral phonic signs—spoken words—are the threads with which we phenomenologically weave ourselves into being and human consciousness.

An electronic musician as well as an installation artist, Caly McMorrow focuses on the auditory as she explores the ontology of the spoken word in Status Update, a transparent sound and light chamber shrouded in shadows. Participants activate the spiraling structure, setting off a cascade of sound and light, by speaking into the antique telephone receiver at its center. They hear the sound of their own utterances moving across space, broadcast singularly at intervals through a series of twenty-seven small speakers arranged in a spiral in a dimly lit corner of the gallery. As each speaker emits the sound of the participant’s voice, a corresponding lightbulb briefly flashes as the words hang for a moment in the air, suggesting that the artist may view words as the sparks of consciousness. Significantly, McMorrow does not stop with the singular speaker. Rather, adapting Facebook’s collaborative style of speaking/writing that unfolds in time as an accumulation, Status Update creates an audio collage of participants’ voices, which, as the lingering traces of consciousness, represent the murmuring sound of humanity.

Artist Statement

I am a sound designer, installation artist, and composer and performer of experimental electronic music. I blend the DIY-driven culture of circuit bending and hardware hacking with a background in classical music and technical theater. I!m inspired by the juxtaposition and merging of old with new; live with automatic; organic with electronic; and creator with audience. Common themes in my work include the mutable nature of memory and history; and alternate versions of the past, present and future. I!m influenced by various aesthetics of retrofuturism and science fiction.

Biography

b. 1977, Minneapolis

works St. Paul

mentor:

Caly McMorrow is an electronic musician, sound designer, and interactive installation artist based in St. Paul. One of few women in the DIY-driven culture of music made with video games and altered electronic toys, she blends these and live-looping technology with a background in classical saxophone and piano to create layered compositions of “ambient glitch.” She is equally at home at a warehouse party or a gallery opening, and has performed and exhibited in varied venues such as the Walker Art Center, the Spark Festival of Electronic Music and Arts (as a performer, juror, panelist, and installation artist), San Francisco’s Noisebridge Hacker Space, The Tank’s Bent Fest, First Avenue and 7th Street Entry, and the Rochester Art Center.

Links

tectonic industries, Perhaps this is the only way of knowing if anything was ever important to you

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“We had never watched Oprah before this, and we were not aware of her power. Some of the programs are solemn and good, and others are just trivial, but it’s all treated the same.”

Perhaps this is the only way of knowing if anything was ever important to you.

For the duration of 2010, tectonic industries summarized from spoken word to text, every new episode of the Oprah Winfrey Show and published the results online. The summary was typed in real time as the episode played, and was published in blog format. A five-sentence summary of each episode was also posted on Facebook, and a 140 character or less summary also posted on Twitter. For the Art(ists) on the Verge 2 exhibition at the Spark Festival, the Twitter-sized summaries of all the episodes viewed to date were displayed scrolling horizontally across the front of the Regis Center for Art at the University of Minnesota.

By transcribing the show, all drama and visuals have been removed for the audience, neutralizing the often-hysterical aspect of the television show. The stream of words extracted from the episodes references media events, trivia, world news, issues close to Oprah, celebrities and wellness tips, forming a time capsule of sorts of the collective preoccupations of the year 2010, as reflected through the media empire of Oprah Winfrey. In this way, tectonic industries want to communicate the necessity of re-examining that which we take for granted, by giving viewers the opportunity to examine our aspirations from the mundane to the fantastical.

At the end of the year, the three streams of recorded information will be available in a limited edition three-part book set.

America through the Lens of Oprah

Ann Klefstad

tectonic industries’ Perhaps this is the only way of knowing if anything was ever important to you is an elegiacally titled text piece that is anything but poetic. It’s a textual account of what will be an entire year of the daytime television talk show Oprah, transcribed as best the artists can, and then projected as text into the night, through the curved second-story windows of the Regis Center.

tectonic industries is Danish artist Lars Jerlach and British artist Helen Stringfellow, who have been collaborating now for over a decade on work that “focuses on the artifice inherent within the creation of the modern myths and belief systems of popular culture, with a concentration on our seemingly endless quest for self-improvement” (from the artists’ statement).

Jerlach and Stringfellow are perhaps “strangers in a strange land.” In Denmark, says Jerlach, there are perhaps 2 television channels. In England, there are more, but media is certainly not the infinite carnival of desire that it is here. Their work relies on an implied distinction between pop-culture artifice, or “artificiality,” which seems to them perhaps hysteric or delusional, and the artifice that is part of all artmaking, from the first chthonic myth to the last biennial.

Their work here attempts, through hard and relentless work on their part, watching every episode of the Oprah show (not something they’d ever done before) and transcribing its language, to outline the true content of the Oprah phenomenon with the white light of the written word—almost literally.

This is a cultural difference, says Jerlach, who teaches at UW-Stout. “My students watch the film, I read the book. If they like the film, then perhaps then they will read the book.”

About his and Stringfellow’s experience of the Oprah show Jerlach remarks, “I think that the made-up world the way we are watching it on Oprah, it is kind of hysterical, it’s artificial, everyone is addressed the same way, the audience is managed. I think that when we just use the language, then it is an equal playing field, and we can see what is being said more clearly.”

But after viewing many episodes of the show, with the knowledge that 70 million people watch it, Stringfellow and Jerlach have acquired respect for the woman who creates it: “We had never watched Oprah before this, and we were not aware of her power. Some of the programs are solemn and good, and others are just trivial, but it’s all treated the same. From child abuse to weight loss, it is so diverse.”

About this mix of the fluffy and the deep, Jerlach says, “We have come to see this, that everything is organized, there is a deep-rooted system, calculated. She is a phenomenal person, a phenomenal actor, she can pretend that everything is as important as everything else. She is America’s mother.”

I am not sure I trust the very European faith in text over spectacle, and the implied assumption that most people’s preference for spectacle makes them easily gulled. To my mind, the lifting of text from its context of affect and emotion, and from its source in the very real physical body of Oprah Winfrey, is something of a betrayal.

Europeans may not understand fully that there are reasons that text is not as trusted here as it may be in Denmark or England. Our culture is finally publicly acknowledging its hybridity, its multicolored and multicultural nature. Oprah is the queen of popular culture along with the bleached Lady Gaga; biracial Obama is our president.

American culture is composed of the gifts of Europe, yes, but also of the gifts of Black culture. Complex ideation here may not be primarily a matter of text; mind and body are less separate and the body does not carry the Cartesian stain (see the Eurovision song contest for proof of this difference!). In Black religious traditions group emotion is traditionally a great source of loving strength, not hysteria. Traditional Black bodily aesthetics don’t reject flesh. Many of the aspects of Oprah that have been flensed away by the analytical scalpels of tectonic industries are not mere obfuscation or hysteria; they are containers of meaning.

That said, to read the flow of language in the night, across the clean arched glass of the university art center, is quite wonderful. The alienation of the words—that is, the coolness of their presentation, the relatively slow speed at which one assimilates them—this does make them amenable to thought in ways very different from experiencing them on television.

The idea of meaning itself is, by any reasonable account, artifice—it is constructed. Human beings are the species who can make shit up. That’s who we are. Playing in the same neighborhood is the play The Oldest Story in the World—the tale of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, and his friend Enkidu. Four thousand years ago people constructed this lie-that-tells-the-truth. “Artifice” is the root word for “art”. To attempt to reveal truth by stripping artifice is, perhaps, naïve; truth can only be gotten at tangled up in all the lies that give it life.

Electronica and virtuality bring us, again, to the root questions of humanness: Can we create our selves? Can we create our own world? Are we at the mercy of our creations? Are they, rather, under our control? What do we want from what we make?

Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.

Artist Statement

tectonic industries examine the artifice inherent within the creation of the modern myths and belief systems of popular culture. Ultimately these created worlds become a pervasive form of reality, universally meaningful within the mainstream collective memory. At the heart of the investigation lies a fascination with visual, literal, televisual and cinematic pop culture that centers on appearances and narrative. Borrowed language is distorted, manipulated and morphed to heighten the artificial. Referencing immediately identifiable cultural signifiers in conjunction with our seemingly endless quest for self-improvement, tectonic industries create mixed-media installations that scrutinize our all-encompassing desire for instant gratification and immediate satisfaction.

tectonic industries

tectonic industries is a collaborative art partnership of the Danish artist Lars Jerlach and the British artist Helen Stringfellow. The members began collaborating in 1999, while pursuing their MFA’s in Sculpture at Edinburgh College of Art, Scotland. In 2001 they relocated to the USA, and they currently live in the Twin Cities.

tectonic industries has had solo exhibitions at Franklin Art Works (MN), artDC (DC), and ONEZERO Projects (UK), and have participated in group exhibitions and festivals including The Soap Factory (MN), Contemporary Art Institute of Detroit (MI), Urban Institute for Contemporary Art (MI) and You Are Here Festival (UK).

Links

Tyler Stefanich, Re-Presented Narratives

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“The resonance of his piece goes beyond this insight, into the elusiveness of relational meaning—as soon as you seize it, it vanishes.”

Re-Presented Narratives

Re-Presented Narratives roots itself in a performance from almost a year earlier in which I sat down with individual viewers, one at a time, and recalled memories of growing up. Simultaneously, five film projectors were showing looped film clips of appropriated, re-recorded home movies found on the Internet. As the films continued to loop through the recounting conversation, they began to deconstruct, and was echoed by changes / mutations taking place in the spoken narrative from individual to individual.

Re-Presented Narratives is made up of four chairs that face four large screens on four walls of a room. Small speakers dangle from cords at ear height by each chair. The chord runs from the speaker to the seat of the chair. Each screen shows individuals who experienced the performance from nearly a year ago, recounting their memories of it. The speakers’ volume is faint and audience members must hold the speaker up to their ear to hear the voices.

When people sit in a chair a circuit is created—between chair, person, speaker and story. When the circuit is activated, the legibility of sound and image become inverted and distorted. Each engagement with the piece automatically creates another a degraded copy in a series of copies, creating echoes of the original telling. The only way to hear a lucid version of the narrative is to remove one self from the circuit, by standing.

Elusive Knowledge

Ann Klefstad

Stefanich’s Re-Presented Narratives is a subtle piece that perhaps needs repeated experiences as well as, maybe, better didactics (Christ, I never thought I’d want that!) to get the point. And there is a point here.

Four chairs face four large screens on four walls of a room. Small car speakers dangle from cords at roughly ear height by each chair. A cord runs from the seat of each chair. Each screen has a moving face on it, a video of someone speaking intently to the camera—or, of course, to you. The speakers contain their voices, pitched just low enough that you have to seize the speaker and bring it to your ear—it’s like someone almost-whispering into your ear, for you only, an utterance in confidence.

Then when you sit on the chair to relax into the story, the image before you flattens into huge distorted pixels and the voice from the speaker blurs and garbles. So you stand, and all is clear. There’s discomfort in the standing, but relaxing into the chair eliminates real communion. Why?

Tyler Stefanich explains: “Nine months ago I did a performance. I took appropriated video from the internet of family movies and I rerecorded them onto Super 8 film. I showed the films, and when people came to see them I talked to them about growing up in northern Minnesota. Then, for the Art(ists on the Verge) piece, I called them, the people I had talked to. I asked them to let me post videos of them on YouTube, talking about what they remembered of the films. That’s who the people are, on the screens.

“The chairs have monograms written in gold in Garamond type, the person’s initials and their birthday. When people sit on the chairs it inverts visibility, when you sit down the image and sound gets more distorted. Every time someone engages with the piece it creates another copy in a series of copies of the videos, which get more and more distorted with each generation of copy. The only way to hear the narrative is not to be part of the circuit.”

Stefanich notes that his original performance was very confidential and intimate, and that the story changed each time he told it. That process of memory is replicated in the chain of increasingly distorted versions of the videotape evoked in this installation.

What’s the larger import of this pair of performances? It’s a subtle thing, but I think obvious— though not easy to express. This is the kind of thing that actual sensory experience can do—it can quite accurately seize on things we all recognize but have no language for, and can put these things within reach.

Stefanich alludes to the narrow perspectives we each have on our own realities, and how removing oneself from “the circuit” can clarify meanings by broadening one’s perspective. But the resonance of his piece goes beyond this insight, into the elusiveness of relational meaning—as soon as you seize it, it vanishes.

Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.

Artist Statement

My work focuses on the idea that as a culture, through the use of the Internet as medium and other new technologies, we are perpetually regenerating a digital semblance of the present and in turn the past. My practice as a multi-media artist revolves around the structures of private and public history, culture, memory and interpretation. There is a threshold where events and experiences no matter how vivid, become abstract and one’s view towards one’s own history becomes apathetic. My work often finds itself in the in-between spaces of these structures and roots itself in many different disciplines. By blurring boundaries between past and the present, and by fusing the old and the new, the recorded and the remembered, my work questions the originality of what is being presented and challenges perspectives we each have on our own realities.

Tyler Stefanich

Tyler Stefanich received his BFA from Minneapolis College of Art and Design in Web and Multimedia. He had the privilege to travel to the Burren College of Art to stay there (to study) for 4 months. This allowed him easy access to the rest of Europe and traveled to such places as Scotland, Germany, and Italy. His work has been shown in such exhibitions as Phase Shifts, Made at MCAD, and Spark Festival. He also has been a Jerome Semi-finalist and the recipient of the Media Art Senior Scholarship, the Northern Lights Fellowship, and the Minnesota State Arts Board Grant.

Website

Arlene Birt, Visualizing Grocery Footprints

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“In a complicated world, Birt’s purpose is to provide clear pictures of that complicated world.”

Visualizing Grocery Footprints

Project Statement

TraceProduct.info, the online component of the installation at the Spark Festival, Visualizing Grocery Footprints, aims to visualize the narratives behind the ubiquitous objects that we interact with everyday as consumers. It focuses on the ways in which these products connect us to the larger world.

By bringing the attention of the shopper to the detailed and factual backgrounds of their everyday choices, TraceProduct.info seeks to inspire people to understand more about how their individual purchases impact global environment and society.

Where It Comes From

Ann Klefstad

Arlene Birt’s Visualizing Grocery Footprints is a data-driven and interactive installation that enables the customers of a (at the present moment) fictional grocery store to see the points of origin of their food purchases by looking at a screen at the checkout that contains a world map with icons of their purchases located at their sources, or by reading their receipt. It’s meant to fit seamlessly into existing systems for scanning food items and seeing the scanned information on screens.

The piece is, as Birt says, “future-focused,” because at the moment there is no way to easily incorporate the data needed into the scanning system used by grocery stores. In the near future, however, she says, information on food origins may well be a required part of the UPC coding stores use, and then her system could be widely implemented.

Birt is a specialist in devising ways of visually presenting information. In this case, her solid and simple way of transmitting to store patrons the locations from which their food purchases derived has great rational appeal. We all know, foggily, that our food often comes from a long ways off. Myself, being old and all, used to think of this in romantic terms—just think! This banana was hanging on a tree, upside down, in a hot green jungle just a week ago, and now I’m eating it while looking at a thermometer saying 50 degrees below zero, before wrapping up in 6 layers of wool and tromping off to school. That kind of thing.

Is it Birt’s purpose to get us to swear off mangoes? I try to eat local but I live in northern Minnesota. One reason my ancestors left Norway, I’m guessing, is that they got sick of eating white food.

No, says Birt, she is not a proselytizer, for eating local or for anything else.

“My purpose to communicate information about sustainability,” she says. “I don’t want to force people into decisions. Sustainability is different in every context. It’s important that people develop an understanding that can feed sustainability for their whole lives.

“Someone could use this tool to say, ‘I’m only going to eat things from halfway around the world!’ And this isn’t right and wrong. I want to provide information that people can use, and help people understand the big picture.”

In a complicated world, Birt’s purpose is to provide clear pictures of that complicated world.

The biggest part of the work, says Birt, was the coordination involved: “I had to research the existing system of supply, supply-chain databases, cash register software, and write code for all this.”

What she created was the concept of instantly available information on origins of food, as well as the interface that would pull the information and make it useful. Work that moves along the border between what we think of as “art” and what we call design is immensely appealing at a time when systems of information so desperately need creative attention.

We are now in a time when there are vast amounts of raw data available, but very little of it is incorporated into the kind of transparent, usable system that Birt has devised. Between polemic and data there is something like usable information: we need to find ways to create more of it.

Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.

Artist Statement

I am fascinated by the idea that we are endlessly tied to the world through the objects that we consume. Small, seemingly inconsequential objects populate our every-day, and yet the intricate life stories of these objects are hidden from the eyes of their present consumer.

I aim to visually explain the significance of the everyday within the context of the big picture in order to engage people in their role as consumers. I am driven by the idea that when people become engaged with—and can interact with—the stories behind their purchases and daily rituals, they can create a personal connection, from which they can understand their own role in social and environmental sustainability. This theme has emerged from my own varied background: work and study in art, journalism, advertising, sustainability, graphic and interactive design. All of which have provided me with experiences that have greatly informed my artistic process; including sorting through complex information, and working through multiple visual iterations and applications of a project.

Because many voices are present in the backgrounds of each topic I explore and in the creation of each project, it is difficult for me to claim ownership of my work as “the” artist. The outcomes belong to the context from which they came. In this sense the boundaries between art, design, commerce, and technology blur and intersect in my work: real-world static data plays out into more emotionally charged, collectively visual, stories.

Arlene Birt

mentor: Piotr Szyhalski

Arlene Birt is a visual storyteller, artist and information designer. Arlene’s work visually explains the significance of the everyday within the context of the big picture in order to communicate the impacts of sustainability to consumers.

Arlene received a Fulbright grant to the Netherlands to research visual communication methods to “explain” sustainability, and a Masters in Design from Design Academy Eindhoven (NL). Now based in Minnesota (US), Arlene teaches visual information design and works with companies aiming to improve their sustainability communication.

Her work on sustainability, which rides the line between art and communication, has been featured in Creative Review (UK), U.S. News and World Report, BusinessWeek.com, worldchanging.com, SEED magazine, and at the Barcelona Design Museum.

Links

Kyle Phillips, Indexical Architecture

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“The idea changed into making a room that contains memories, and that creates itself out of the experience of people who spend time in it.”

Indexical Architecture

Indexical Architecture is an installation exploring the transient qualities and expectations of inhabiting a space. We live our lives moving through these spaces, experience our joys and our angst in these rooms, but don’t expect that there will be any manifestation of our presence. The rooms we commonly occupy have no method of transferring their own life story to those that visit.

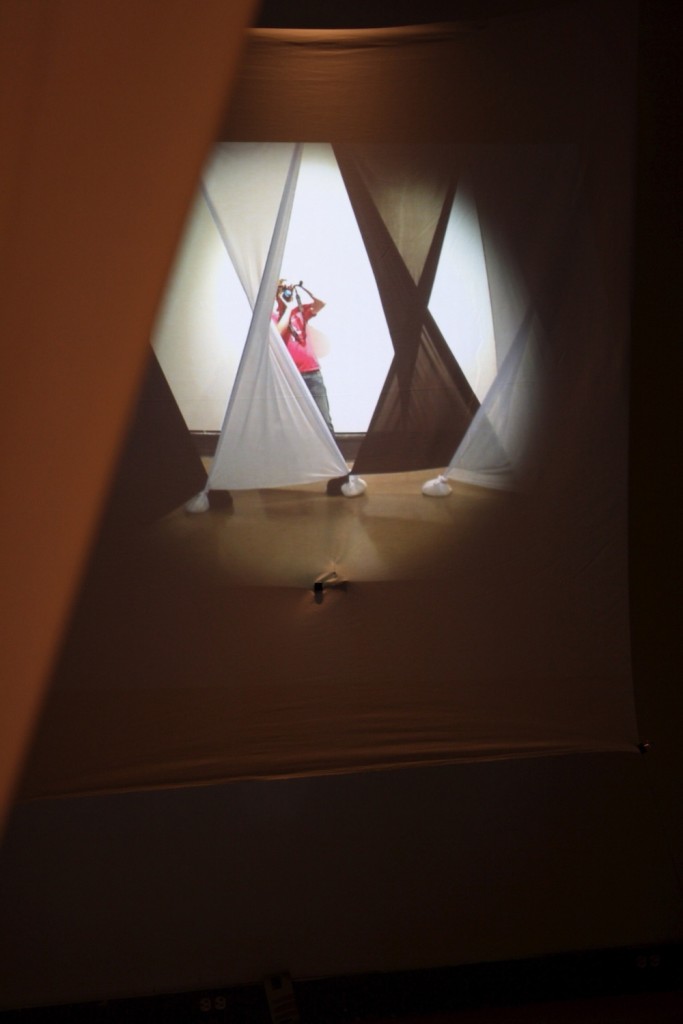

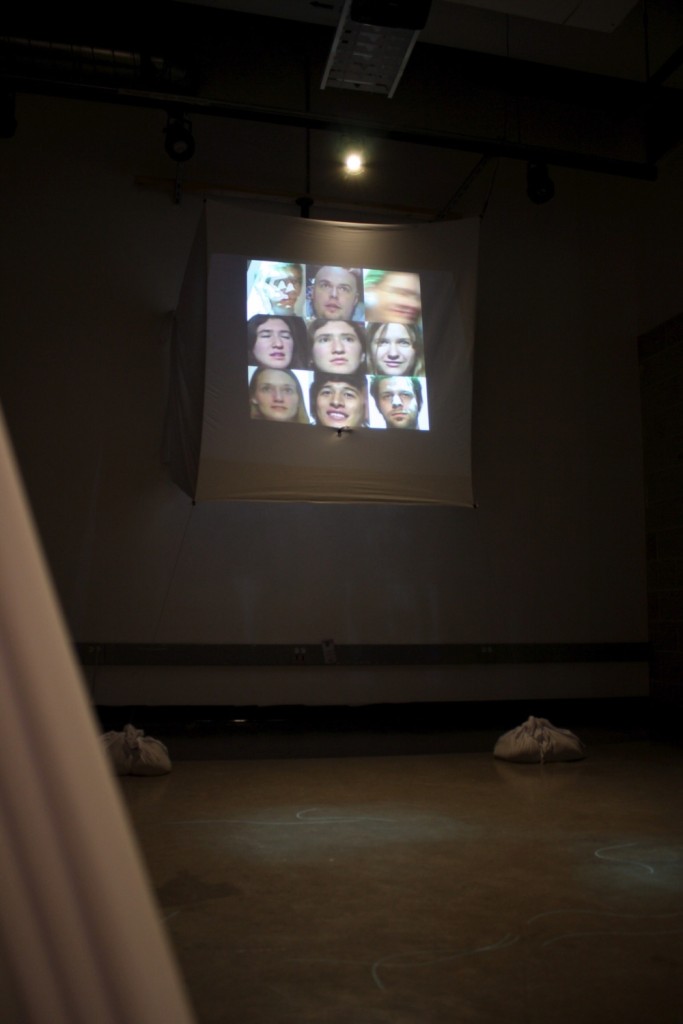

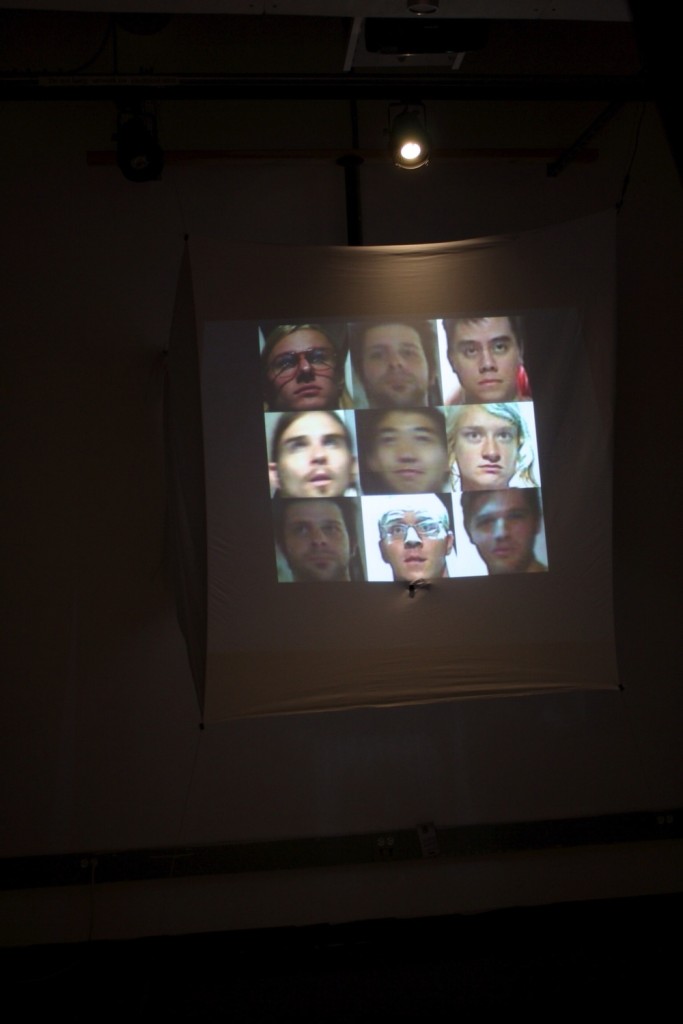

Indexical Architecture is a space imbued with memories. The space is proactive about recording its history as a method of revealing its own identity. Beckoning for a visitor, the entrances play the conversations of those that came before. The ones that enter are faced with fabric draped from the ceiling and weighted to the floor with sand. They can either curtail their exposure by hiding behind this division or they can confront the center of the room. There in the center of the room will either be a mirror image of the room or a grid of animating faces of the room’s previous visitors. As a participant’s face becomes visible, it is replaced with the face of another and simultaneously it is recorded to be displayed for others later. As visitors move around the space they may notice streaming lines of light that seem to chase them along the floor. The lights represent a dynamic visualization of where in the room people most inhabited it. The room aims to be detailed in its own evolution, to reveal itself wholeheartedly, and to make every person it meets a part of a larger shared narrative.

A Room that Remembers

Ann Klefstad

I had the devil of a time finding Indexical Architecture by Kyle Philips; it was in a critique room abutting the gallery. In its solitary room the sounds of other works don’t intrude, which is good. Its sound and visuals are subtle: In a sort of matrix of black and white fabrics twisted into triangular pillar-forms, a box of white fabric holds a projection of the room which is collected by a small camera at its center. Entering, you appear on this screen—and a second later, another face, in a square, moving, speaking, is superimposed on your own, and travels with you as you cross the space.

You can defeat the facial recognition software by shielding your face with a piece of paper. Philips said that people found many ways of playing with the facial recognition software—one guy wearing a T-shirt with Dr Dre’s face on it took off his jacket and started doing a kind of bellydance; others made faces or performed gestures. The camera stored all this up, and projected the memories of past visitors to the space on the mugs of those who had just arrived. Again, this is a subtle piece, and the startling and visceral effect of the superimposed faces is real—but it would have amplified the piece to have more context.

For instance, the piece incorporates three systems of memory: the facial recognition system, relying on the front-mounted camera; a spatial recognition system using an overhead infrared camera that remembers where visitors stood, and creates a kind of cloud of light at favored spots; and a sound system, with a mike and speakers. The latter two sets of memories were not easy to perceive if one did not know to look for them.

Philips spoke about how his intentions for the piece changed as it developed. He had done a version of it for Art-a-Whirl, using only the facial recognition system. He noted that people were reluctant to enter the room and engage with the space if they could “get” the piece from the doorway. So he wanted to find ways to pull spectators into the room, because the idea of domestic spaces, which witness so much life but which remember almost none of it, was the originary thought for the work:

“I had an interest in the quality of occupying space—there’s usually no proof that you were there. Partway though the project, I saw a house from the 1930s. More than one generation of the same family had grown up in this house, and there was relatively no sign of all of the life that had been there, all the experience. So I wanted to see if a room had the ability to remember all the things that had happened in it, and could tell people about it.”

He started out with the idea of an empathetic living room, a room that could, it seems, feel for its occupants. But, in part due to the non-domestic nature of the space available at the Regis—the bare, hard-surfaced critique room—he decided that an indexical space—a space that archived its occupants—would work better.

“The idea changed into making a room that contains memories, and that creates itself out of the experience of people who spend time in it.”

The pillars of fabric arose from the necessity of creating zones in the room, and the need to modulate the space to entice viewers to enter, and then to exit at a different point.

By the end of the show, the hard drive containing the room’s memories had several hundred thousand images on it—a long memory. One wonders what the room thought of us all.

Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.

Artist Statement

My work explores responsive environments, collaborative toolsets, and social observation. Through the use of embedded sensor technologies, I make spaces aware of its inhabitants and allow people to engage and explore the connection between themselves and the system they find themselves within. I create tools, objects or installations, which allow each participant to produce something unique and leave their impression. My goal is to create a spectacle and a personal memory, to heighten the participant’s awareness of the current moment. My projects exploit the public’s inner feelings related to variable personal space or sample information of global viewing trends to get a pulse of where our culture’s interests are strongest. The projects provide value by way of the people using them. They wait to be played with and are at participants’ beck and call, serving as a source of wonderment and existing in a feedback loop of personal expression and analysis.

Kyle Phillips

mentor: Christopher Baker

Kyle Phillips is an Interaction Designer creating interactive installations related to data visualization, generative compositions and web communities. Much of Kyle’s work explores the societal constructs that help define our contemporary culture. His installations critique public and transitory spaces, societal choices and cultural interests. He takes an optimistic stance on the increase of embedded technologies in our daily landscape and finds provoking ways to leverage them and create a shared narrative.

Kyle’s projects have been featured in The New York Times, Communication Arts, Gizmodo and .NET magazine. He has been profiled in Screen, Web Designing and Hitspaper magazines (Japan) and published in the book Vormator: The Elements of Design. His work has been exhibited at the Science Museum of Minnesota, Regis Center for the Arts (Minneapolis, MN), Union Square (Manhattan, New York), M.H. de Young Museum (San Francisco, CA) and Adobe System’s headquarters (San Jose, CA).

Links

Emily Stover, General Delivery

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“Our mailman is privy to intimate details about our day-to-day struggles and triumphs—but anonymously, discreetly so.”

General Delivery

Every day, the U.S. Postal Service navigates our neighborhoods and enters our personal territory, connecting each home to a larger and time-honored system of physical information delivery. Postal carriers perform a quiet role in our communities, viewing the settled terrain in a particular way. They see our houses and yards, observe interactions between neighbors, and get to know our comings and goings. In spite of the government’s infiltration of online communications, the postal carrier is still an accepted, if not appreciated, character in our daily routine. E-mail, cell phones, and social media now allow messages to be sent instantaneously, yet the USPS perseveres in delivering our cards, invitations, and announcements through time and space, right to our front doors. Not even the digital era stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.

General Delivery explores physical and digital forms of communication through an interactive gamelike scenario of sending and delivering messages. At a private writing desk, visitors create handwritten notes to send to a specific location within the gallery. Though digital images of the writings are uploaded to the “cloud,” the correspondence reaches its physical destination only when delivered by another player who inhabits the role of a carrier. These characters don a uniform and set out in search of delivery points throughout the exhibition. Technology embedded within the costume activates a projection of these communications in the space, making the message visible only when a carrier is present to reveal it. The unseen system that conveys our words, whether they are mundane or profound, is more than dropping a letter through a slot or pushing the send button: it is an essential service ritual, a daily delivery dance, that connects everyone to everyone, wherever they may be.

Programming: Kurt Froehlich

Garment design: Carly Schön

Empowered by your uniform to activate …

Susannah Schouweiler

Emily Stover calls herself an “accidental artist.” An architect by training, in recent years she has gravitated toward collaborative social practice, exploring the intersections of design and community-building. Her creative interest tends toward play with our personal relationship to the spaces we inhabit—the ways we imbue familiar places, specific rooms, and centers of activity with personal memory, meaning, and affect simply through the activity of dwelling in them over time.

Stover is fascinated by the shifting boundaries of personal space, how occupation and time spent in a given area might alter one’s sense of ownership. That’s where her interest in her neighborhood postman began: “He’s a person behind the scenes, but intimately connected to our neighborhood,” she says. “In a real sense, he’s as familiar with the homes that make up his route as the residents who live in them. And by walking its sidewalks every day, the same way, he sees the neighborhood as a whole and inhabits it in a way no one else quite does.” For a postman, a particular route acts as both workplace and occupation. The postal carrier is a key component of the social connective tissue that ties each home to the outside world. Our mailman is privy to intimate details about our day-to-day struggles and triumphs—but anonymously, discreetly so.

With General Delivery, Stover wants to give viewers a chance to see what it’s like to play the postman’s role in The Soap Factory. The physical presence of the project is minimal. Along one wall is a line of handsome gray, hooded cloaks on hooks. A lovely old writing desk sits nearby, enveloped by a Brazil-like enclosure of cubbies containing scattered bits of paper. On the desk are some pens, and inside the cubbies all around you are stacks of postcards, awaiting your handwritten messages.

The postcards at the desk are divided into five categories according to spatial zones in the gallery building. Each zone’s designated postcard offers a thematically appropriate set of writing prompts. For example: write a letter for the Office, and you might pen a message to your younger self, or to your boss or coworker. Compose a message for the Toilet, and you could address your own waste. You have the option of writing similarly tailored missives for the delivery zones Front Door, Neighbors, and the Underground (i.e., The Soap Factory basement).

Finish your postcard, and submit it for delivery by way of a drop slot located at the desk. Insertion of your postcard into the slot prompts a whir of purposeful-sounding audio, signaling the message’s transformation from analog form into digital bits and bytes. A camera tucked inside the drop box captures an image of the postcard, then translates those pixels into code, which is sent to the Internet cloud. There it is sorted by zone and put in the virtual hopper, where it awaits distribution to various delivery stations unobtrusively tucked throughout The Soap Factory.

Grab a cloak, put it on, and pull up the hood, and you become the anonymous postman, empowered by your uniform to activate, and read, randomly selected audience-submitted messages.

Stover says, “I am interested in the postman as a neighborhood connector, and in the tension between a physical and digital delivery of information.” But General Delivery isn’t primarily about modes of distributing messages. The heart of the project is harder for Stover to pin down, but she believes it’s somehow entangled with her ongoing fascination about how closely people identify with their built environments, how much of our own stories—our very sense of self—we encode in the structures we inhabit. There’s an intimacy between person and place, and through the playful interactions of General Delivery Stover tries to articulate the textures of this relationship. “I see The Soap Factory, in this context, as a complicated spatial representation of us, of our lives—who we are, how we live, what associations and meaning we make from the places we move through on a regular basis.”

Artist Statement

By gathering people around temporary transformations of public space, I create opportunities for social interaction and alternative explorations of our shared landscape. We may search out new experiences, but we are often unaware of meaningful possibilities that already surround us. A walk on the same path may appear unchanged if we pay no attention to the subtle differences that breathe life into a seemingly inert environment. A slight shift in perspective can turn a stroll into an adventure and ordinary encounters into theater.

I use elements of design, technology, and performance to construct sensory and collaborative experiences in public space, exposing the power of our everyday surroundings and social systems. Though these spatial interventions are varied (including a mobile sauna on a frozen lake, a structure for making and sharing filled dumplings in the Wisconsin farmlands, and a gong in a parking garage), each strives to create a sense of wonder and communion with and within the environment. I want to inspire individual moments of curiosity that multiply and eventually overrun inattentiveness. These new connections and understandings, though physically intangible, can become the source material for larger and more concrete changes to our structures for living.

Emily Stover

b. 1977, Urbana, Illinois

lives in St. Paul

mentor: Abinadi Meza

Emily Stover is a designer and public artist who works with temporary architecture and experiential art. In addition to a Masters of Landscape Architecture, she has recently completed projects at the Bakken Museum, the Art Shanty Project, and the Walker Art Center. She has also participated in the Ten Chances artist residency and is a current City Art Collaboratory Fellow through Public Art Saint Paul. She has upcoming shows at the Katherine E. Nash Gallery in Minneapolis and Practice Gallery in Philadelphia, and is currently collaborating on a series of mobile kitchens for the central corridor in Saint Paul.

Links

Peter Sowinski, Autonomous

Written by Northern Lights.mn

“We’re all experts at manipulating ephemeral experiences, and we’re able to focus our attention precisely and only where we want it.”

Autonomous

The act of composition is a natural human impulse; we share a desire to order our surroundings and to control our environments. Consider still life painting, which, at its height, acted as a compositional exercise for artists focusing on form. The genre is closely linked to the much more complex concept of memento mori. Literally translated as “remember that you will die,” memento mori paintings served as catalysts for meditative contemplation.

The primacy of temporary composition over permanent narrative is a common thread in many new media works, and this idea echoes the metaphorical concerns of still life. In Autonomous, I hope to reveal and explore the tension between the arrangement of these very aestheticized objects and the metaphorical weight of still life as represented in the video projection, examining our tireless (but hopeless) attempts to compose and control every detail of our lives.

I grapple with these ideas by inviting each viewer to compose a still life, one whose consequential reaction is unexpectedly short-lived. By manipulating the sculptural objects, viewers will tune a staticky video feed, but even a seemingly stable moment will find a way to return to chaos. The piece rewards motion and play rather than fixity and perfection.

The overarching question of who controls this piece is essential. While the viewer’s input is absolutely necessary, this is not a true collaboration. The viewer chooses from a selection of objects and images I have created, so this choice is actually circumscribed. This question of control is a larger metaphysical quandary, echoing the issues of memento mori.

We’re all experts at manipulating ephemeral experiences …

Susannah Schouweiler

A large white pedestal sits empty in a self-contained gallery-within-the-gallery. As you walk into the space, along one wall are shelves filled with an assortment of decorative sculptural objects. They are made from natural materials, mostly—simply carved and artfully rough-hewn wood pieces, some copper and frosted glass. They have a genteel, vaguely midcentury design look—the sort of high-end knickknacks you might find dominating an end table in some tony urban loft. Behind the pedestal, you see a projection of something like static, visual white noise.

The empty pedestal is an invitation: take some of the sculptures off the shelves and arrange them in a composition of your own. Do you see anything you like? You notice a sound, a bit like theremin, as you place objects around the display space; you see the static projection appear to visually respond to the objects. Finish your composition, and the projection switches to a video clip: ten to fifteen seconds of footage of a still life arrangement, maybe shot dead-on, perhaps rotating and shown from various angles. You could see one of three hundred to four hundred possible still life clips, a generous range of conventional favorites in the genre: a display of empty vases, or perhaps a spray of dried or fresh flowers, or maybe a bit of string unraveling from a ball of yarn. There are clips showing still life arrangements of vintage tools, timepieces, and things from the kitchen: cups and plates and jars; fruit arrangements (both rotting and fresh); still-bloody cuts of meat ready for the pot—a skinned rabbit, maybe a plucked chicken. Seeing these old-fashioned still life tropes rendered not as fixed mise-en-scènes but as moving images is unsettling.

Peter Sowinski’s installation Autonomous is visually minimalist—just the shelves of chunky objets d’art, the awaiting pedestal, and the projection screen. The tech connecting these components is hidden from view, but exquisitely responsive and complex in its responses.

Sowinski makes his living as a furniture craftsman. Explaining his inspiration for Autonomous, he says, “I’ve been struck by how specifically we control our media. We’re all experts at manipulating ephemeral experiences, and we’re able to focus our attention precisely and only where we want it.” Especially as we spend more and more time online, “we can feel our impulse for choice to the max.” We fine-tune our news sources to suit our interests and inclinations. We carefully “curate” the content of our Facebook pages and Twitter feeds, and we painstakingly craft a social media presence to showcase just what we want the world to see about our lives. It’s a shopper’s paradise: online purveyors set before us a wealth of consumer goods for every mood and budget, solutions to problems real and manufactured, all cheaply available and just a click away.

“All these superficial aesthetic choices,” this urge-to-decorate and customize—it may feel like empowered decision-making, but all those granular, cosmetic choices do not amount to real agency, Sowinski argues. It’s just a distraction, a coping mechanism that we mistake for our actual lives. “I wanted to see what it would be like if you offered people an unfamiliar interface—in this case, a sculptural interface—in which decision-making is invited but ultimately outside their control.”

“We so rarely get to step outside the framework of all these inconsequential choices, outside the feedback systems we’re used to,” Sowinski says. “Here, the still life provides a ballast. The genre is familiar enough to be accessible, but not very common anymore.” The imagery taps into a lot of well-worn narratives—about mortality and the passage of time, especially—but “it does so obliquely,” maybe offering an occasion for fresh reflection on choice and agency.

Artist Statement

My sculptures and installations revolve around dual fascinations: with technology and a deep interest in material and techniques of craft. By technology, I mean everything from simple mechanical contraptions to modern computerized apparatus. I seek to create art that merges the simple beauty of a well-made object with technical sophistication, imbuing the objects with their own agency. These charged works engage complex ideas, from questioning the role of machines in our lives to pondering the seemingly universal force of entropy.

Made largely of steel, wood, and electro-mechanical elements, my projects often invite the viewer to physically interact—by turning a handle to power a machine or by participating with a slyly nonfunctional drinking fountain. At times I use technology to make my work kinetically active and to create a certain artistic gesture, such as striking a drum, drawing an electrocardiogram line, or flashing the bare bulb of a coiled work lamp.

The primary goal of my artistic practice is to inspire more considered living through aesthetic experience. There is something radical about a well-executed art object, because its value lies in the ineffable. Ultimately, the art object’s defiance of traditional valuation hints that we, too, can defy the conventions and expectations that dominate our lives.

Peter Sowinksi

b. 1983, Socorro, New Mexico

lives in Minneapolis

mentor: Chris Larson