Aaron Westre, City Fight!

“At a basic level, City Fight! is an experiment in making cities into playthings.”

City Flight

My work emerges from the recombination of ideas from architecture, software development, biology, physics, social sciences, and other domains. I am educated as an architect and identify primarily with the discipline of architecture, but my medium is software. The software applications I create are tools that allow people to playfully engage with the creative process of design. They incorporate techniques from video games, the sciences, and social media to arrive at novel 3D design tools that act as a counterpoint to traditional design software. I am exploring techniques from multiplayer/networked video games, biological growth processes, machine learning, social software, and crowdsourcing to build creative, participatory design tools.

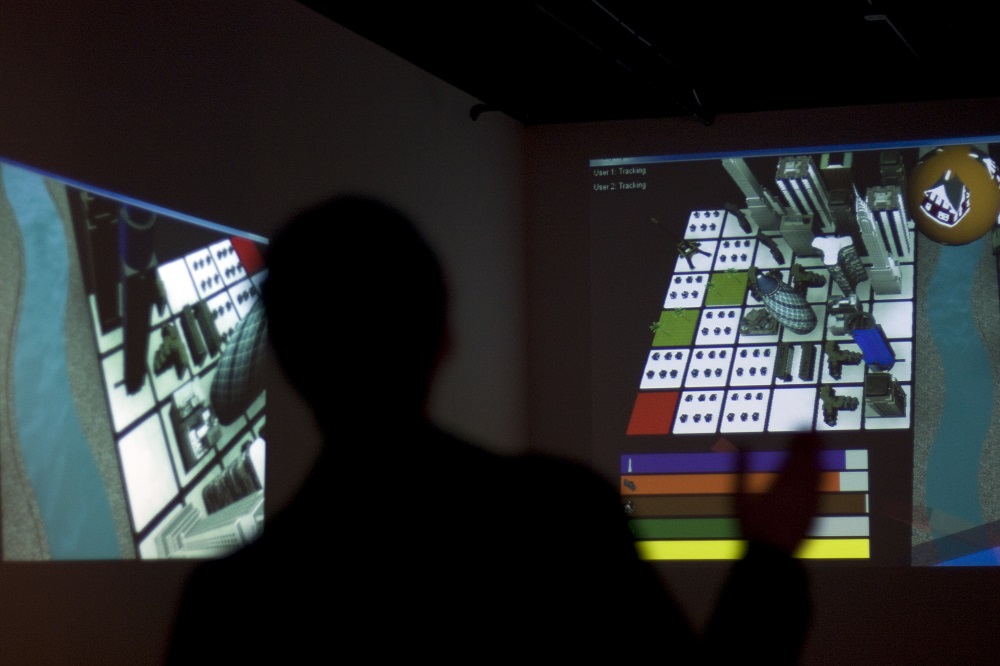

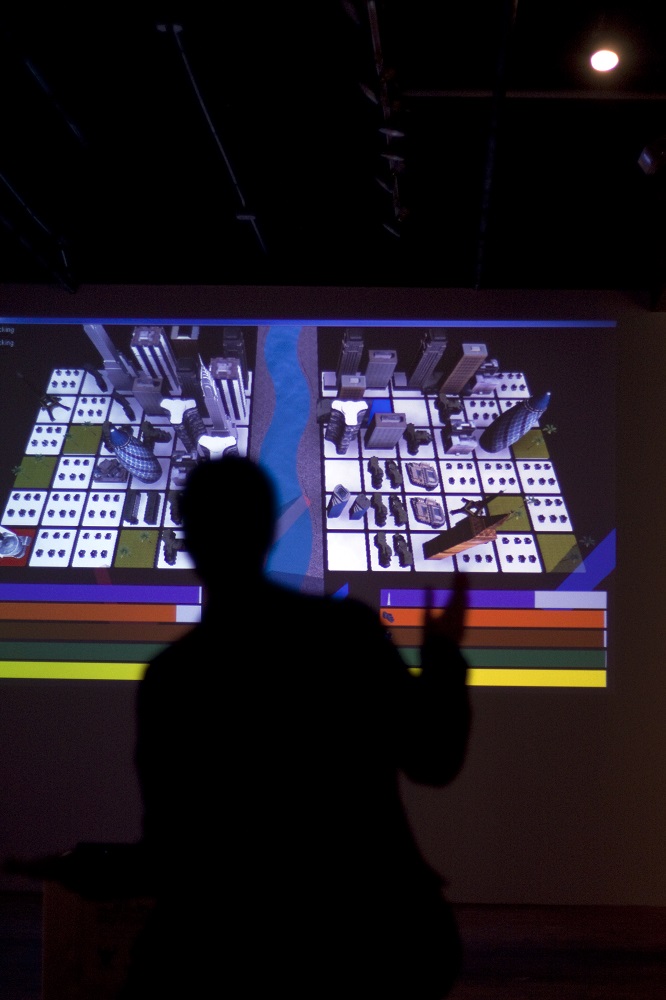

City Fight! is a video game that involves two players standing side by side facing a large screen. On the screen are two city grids (one red, one blue) separated by a river. Each player’s goal is to build a complete city before his or her opponent does. At each turn a skyscraper, an apartment block, a park, or another piece of a city is launched upward into view of the players. These pieces are colored red or blue, indicating which player needs that piece. The two opponents fight to determine where it will land by using their arms to hit it in the direction of their grid. Once a piece is hit, it falls onto the city grid and sprouts into the Empire State Building, the Eiffel Tower, the Great Pyramids, or another of hundreds of buildings and landmarks from around the world.

Turn by turn, both grids fill with an eclectic assortment of structures, each city forming a unique but oddly familiar assemblage of international architecture. Each player sees an indicator showing the completeness of their city; it notes whether a city needs more tall buildings, more housing, more open space, or other necessary components. Players can sabotage each other by stealing pieces before the opponent can hit them. This theft might help a city, but it could also overcrowd it with shopping malls or parking garages. A bomb launches periodically, giving players the opportunity to blow up part of the opponent’s city or get rid of unnecessary parts of their own. Eventually either red or blue will win by hitting one final piece into place. The winner is treated to an aerial tour of their new city.

At a basic level, City Fight! is an experiment in making cities into playthings. By building in a fast, fun, and humorous way, the seemingly static cities we inhabit may become more flexible and dynamic in our minds.

City Fight! is also about the growth of modern cities. This process is a continual struggle between political, social, and commercial interests that can feel at times random, bewildering, or wonderful. The game creates an environment in which those same emotions can be felt, often in rapid succession. By experiencing the growth of a city in fast-forward, this process can be illuminated in all its messiness, complexity, and absurdity.

Background

Art is relational and interactive, because it is designed to be viewed and is meant to inspire a response. When artists began to use computer software as an aesthetic medium, the relational and interactive possibilities for art expanded. Until recently, interactive computer-based art presented viewers with a keyboard, mouse, or sensing devices that could do little more than mirror the viewer’s image with patterns on a screen. Everything changed with the invention of powerful “gestural interfaces” that now allow viewers to control complex computer functions with the wave of a hand. Artist Aaron Westre uses Microsoft’s popular Kinect controller (one of the most well known gestural interfaces that is the motion-sensing input device for the Xbox 360 video game console) to power City Fight!, his interactive installation on the theme of urban development.

When two viewers stand with hands raised in front of Westre’s installation, the Kinect controller recognizes their skeletal structures and begins to map their hand movements onto game paddles within a gridded game board projected on a large screen. Even though gestural interfaces such as the Xbox and Nintendo’s Wii are only a few years old, we already know how to plug our bodies into these wireless computer technologies, and we enjoy seeing our movements translated into projected spectacles.

The game begins as soon as Westre’s software couples with participants’ bodies. Balls shoot onto the board and land as valuable urban property. Knock a property to your side of the board and your city grows and thrives; lose it to your opponent and weep at your diminished symbolic wealth and prestige. Players throw themselves into the action, slapping, whacking, swatting, and grunting as they maneuver for properties, their actions amplified by loud thumps that sound as game pieces are launched and then land. Of course, no game about urban development would be complete without the opportunity to steal your opponent’s property or the occasional destructive blast of terrorist attack or gas main failure. City Fight! has them all.

Westre set up two screens: one gives a bird’s-eye view of the virtual action, the other runs tight shots of properties as they land on the urban parcels marked on the board. This dynamic presentation of the competition attracts and entertains the audiences that gather to watch the play.

City Fight! is a fun game with a serious message: the business of urban development is messy, chaotic, reactive, and cutthroat. Politicians, special interest groups, and wealthy developers mobilize the capital behind urban building projects and manipulate city governments to write and rewrite zoning codes. Populations are displaced, businesses prosper or are ruined, histories are buried, and fortunes and political campaigns are won and lost in the real game of urban development in the cities where we live.

Artist Statement

My work emerges from the recombination of ideas from architecture, software development, biology, physics, social sciences, and other domains. I am educated as an architect and identify primarily with the discipline of architecture, but my medium is software. The software applications I create are tools that allow people to playfully engage with the creative process of architectural design. They incorporate techniques from video games, the sciences, and social media to arrive at novel 3D design tools that act as a counterpoint to more traditional design software. I am currently exploring techniques from multiplayer/networked video games, biological growth processes, machine learning, social software, and crowdsourcing to build creative, participatory design tools.

Biography

b. 1975, Willmar, Minnesota

works St. Paul

mentor:

Aaron Westre is a software developer working at the intersection of science, art, and design. He received a Master of Architecture degree from the University of Minnesota in 2008 and is now an instructor at the University of Minnesota School of Architecture, where he teaches students how to create digital tools. His research and creative interests lie in building software that allows artists and designers to expand their capacity to create, communicate, and collaborate.