Kyle Phillips, Indexical Architecture

“The idea changed into making a room that contains memories, and that creates itself out of the experience of people who spend time in it.”

Indexical Architecture

Indexical Architecture is an installation exploring the transient qualities and expectations of inhabiting a space. We live our lives moving through these spaces, experience our joys and our angst in these rooms, but don’t expect that there will be any manifestation of our presence. The rooms we commonly occupy have no method of transferring their own life story to those that visit.

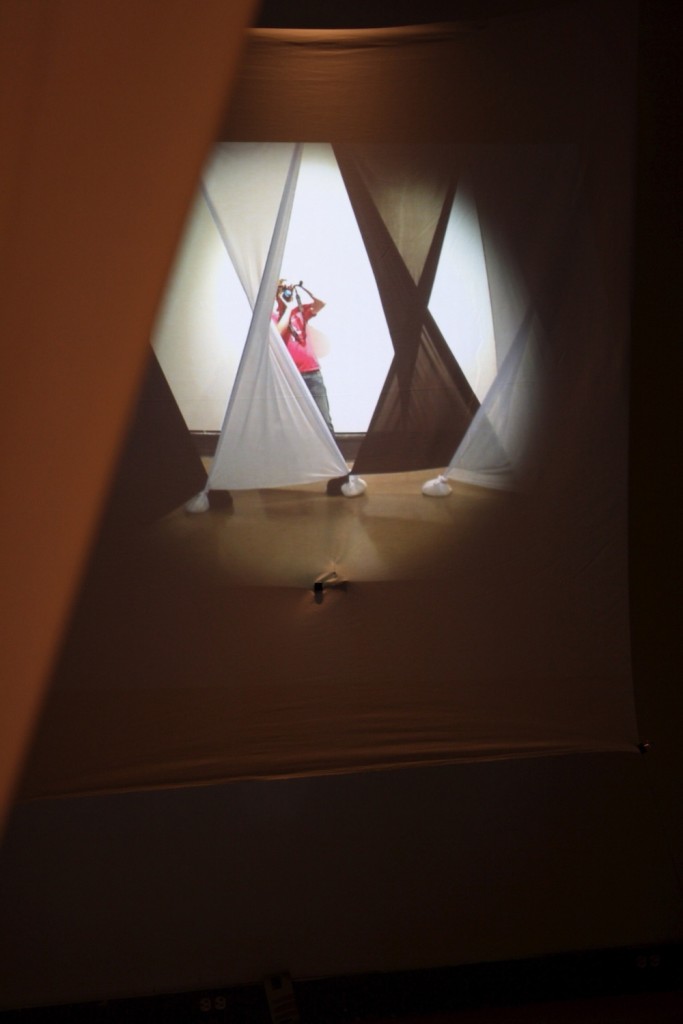

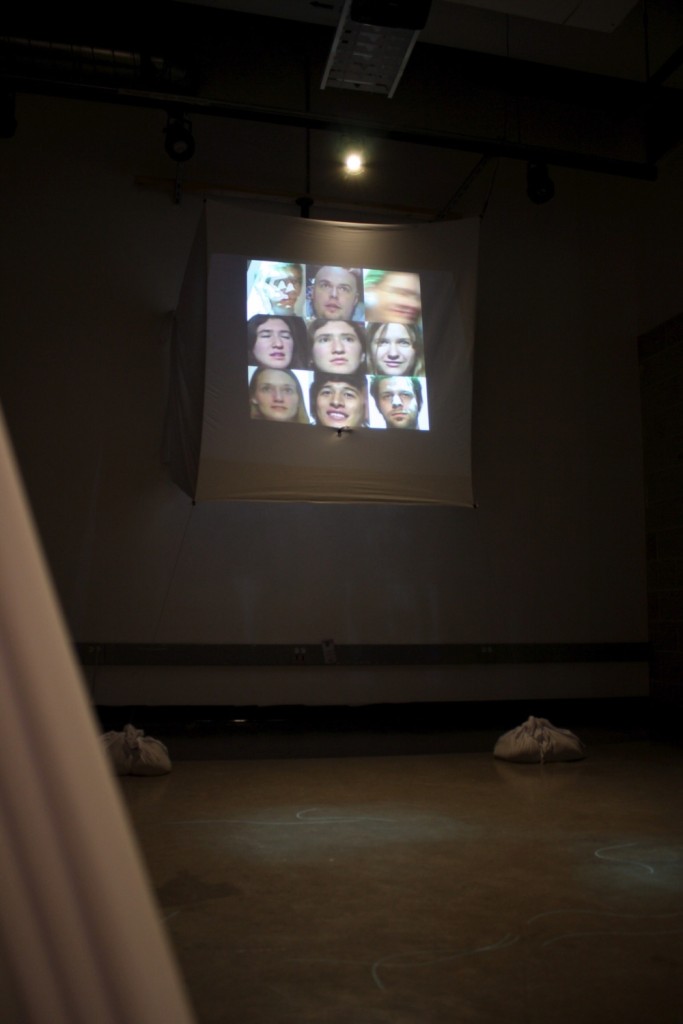

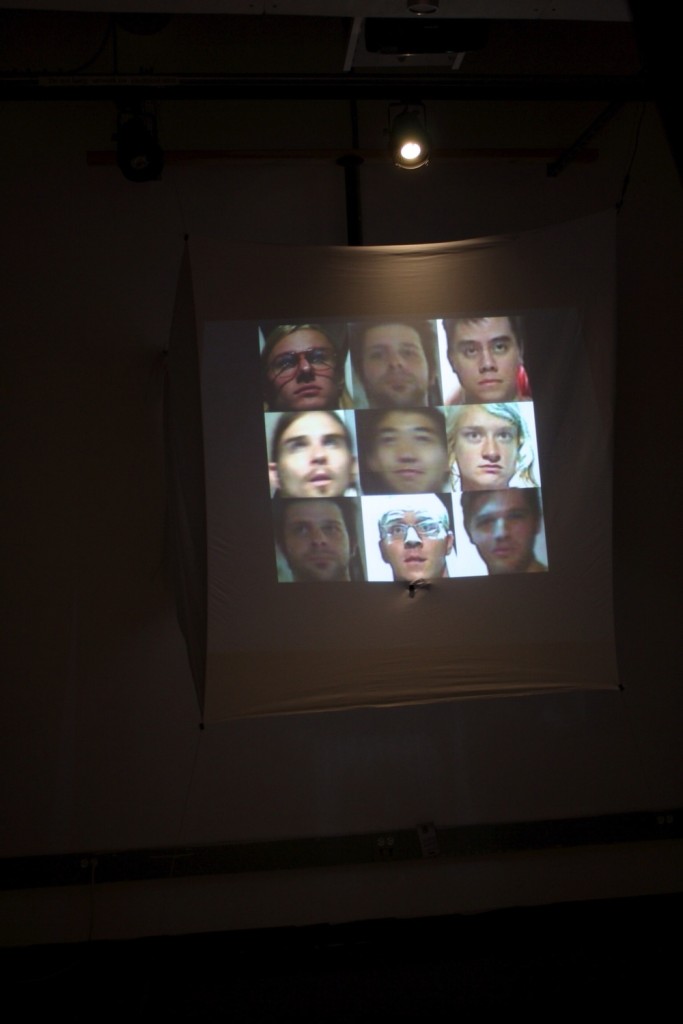

Indexical Architecture is a space imbued with memories. The space is proactive about recording its history as a method of revealing its own identity. Beckoning for a visitor, the entrances play the conversations of those that came before. The ones that enter are faced with fabric draped from the ceiling and weighted to the floor with sand. They can either curtail their exposure by hiding behind this division or they can confront the center of the room. There in the center of the room will either be a mirror image of the room or a grid of animating faces of the room’s previous visitors. As a participant’s face becomes visible, it is replaced with the face of another and simultaneously it is recorded to be displayed for others later. As visitors move around the space they may notice streaming lines of light that seem to chase them along the floor. The lights represent a dynamic visualization of where in the room people most inhabited it. The room aims to be detailed in its own evolution, to reveal itself wholeheartedly, and to make every person it meets a part of a larger shared narrative.

A Room that Remembers

Ann Klefstad

I had the devil of a time finding Indexical Architecture by Kyle Philips; it was in a critique room abutting the gallery. In its solitary room the sounds of other works don’t intrude, which is good. Its sound and visuals are subtle: In a sort of matrix of black and white fabrics twisted into triangular pillar-forms, a box of white fabric holds a projection of the room which is collected by a small camera at its center. Entering, you appear on this screen—and a second later, another face, in a square, moving, speaking, is superimposed on your own, and travels with you as you cross the space.

You can defeat the facial recognition software by shielding your face with a piece of paper. Philips said that people found many ways of playing with the facial recognition software—one guy wearing a T-shirt with Dr Dre’s face on it took off his jacket and started doing a kind of bellydance; others made faces or performed gestures. The camera stored all this up, and projected the memories of past visitors to the space on the mugs of those who had just arrived. Again, this is a subtle piece, and the startling and visceral effect of the superimposed faces is real—but it would have amplified the piece to have more context.

For instance, the piece incorporates three systems of memory: the facial recognition system, relying on the front-mounted camera; a spatial recognition system using an overhead infrared camera that remembers where visitors stood, and creates a kind of cloud of light at favored spots; and a sound system, with a mike and speakers. The latter two sets of memories were not easy to perceive if one did not know to look for them.

Philips spoke about how his intentions for the piece changed as it developed. He had done a version of it for Art-a-Whirl, using only the facial recognition system. He noted that people were reluctant to enter the room and engage with the space if they could “get” the piece from the doorway. So he wanted to find ways to pull spectators into the room, because the idea of domestic spaces, which witness so much life but which remember almost none of it, was the originary thought for the work:

“I had an interest in the quality of occupying space—there’s usually no proof that you were there. Partway though the project, I saw a house from the 1930s. More than one generation of the same family had grown up in this house, and there was relatively no sign of all of the life that had been there, all the experience. So I wanted to see if a room had the ability to remember all the things that had happened in it, and could tell people about it.”

He started out with the idea of an empathetic living room, a room that could, it seems, feel for its occupants. But, in part due to the non-domestic nature of the space available at the Regis—the bare, hard-surfaced critique room—he decided that an indexical space—a space that archived its occupants—would work better.

“The idea changed into making a room that contains memories, and that creates itself out of the experience of people who spend time in it.”

The pillars of fabric arose from the necessity of creating zones in the room, and the need to modulate the space to entice viewers to enter, and then to exit at a different point.

By the end of the show, the hard drive containing the room’s memories had several hundred thousand images on it—a long memory. One wonders what the room thought of us all.

Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.

Artist Statement

My work explores responsive environments, collaborative toolsets, and social observation. Through the use of embedded sensor technologies, I make spaces aware of its inhabitants and allow people to engage and explore the connection between themselves and the system they find themselves within. I create tools, objects or installations, which allow each participant to produce something unique and leave their impression. My goal is to create a spectacle and a personal memory, to heighten the participant’s awareness of the current moment. My projects exploit the public’s inner feelings related to variable personal space or sample information of global viewing trends to get a pulse of where our culture’s interests are strongest. The projects provide value by way of the people using them. They wait to be played with and are at participants’ beck and call, serving as a source of wonderment and existing in a feedback loop of personal expression and analysis.

Kyle Phillips

mentor: Christopher Baker

Kyle Phillips is an Interaction Designer creating interactive installations related to data visualization, generative compositions and web communities. Much of Kyle’s work explores the societal constructs that help define our contemporary culture. His installations critique public and transitory spaces, societal choices and cultural interests. He takes an optimistic stance on the increase of embedded technologies in our daily landscape and finds provoking ways to leverage them and create a shared narrative.

Kyle’s projects have been featured in The New York Times, Communication Arts, Gizmodo and .NET magazine. He has been profiled in Screen, Web Designing and Hitspaper magazines (Japan) and published in the book Vormator: The Elements of Design. His work has been exhibited at the Science Museum of Minnesota, Regis Center for the Arts (Minneapolis, MN), Union Square (Manhattan, New York), M.H. de Young Museum (San Francisco, CA) and Adobe System’s headquarters (San Jose, CA).